API error handling best practices for clear user messages

Learn API error handling best practices for consistent error shapes, safe messages, and a simple method to map server failures to clear UI states.

Why unclear API errors frustrate users

When an app fails, users don’t see “an exception.” They see a blocked task. If the message is vague or scary, they may worry they lost data, did something wrong, or even got hacked. Most won’t try to debug it. They’ll leave, spam the button again, or contact support.

Confusing errors also feel random. One screen might say “Something went wrong,” another shows a long server stack trace, and a third returns nothing at all. That inconsistency makes people hesitate because they can’t learn what to expect. Even if the problem is minor, the experience feels unreliable.

For your team, inconsistent errors create noise. Support tickets get longer because users can’t describe what happened. Analytics fills with ungrouped “unknown” failures. Engineers waste time reproducing issues because the response shape changes between endpoints, or because a 500 is used for everything.

When errors are unclear, users usually do one of three things: retry repeatedly (which can create duplicate requests and sometimes duplicate charges), abandon the flow (especially checkout, signup, and password reset), or contact support with screenshots instead of useful details.

Clear error handling fixes this by standardizing three things:

- A consistent error shape (so every endpoint fails the same way)

- Safe wording (so users get a clear next step without exposing internals)

- Predictable UI behavior (so each error maps to a known state like “try again,” “fix input,” or “sign in again”)

What a good error should do (for users and for your team)

A good API error isn’t just “something went wrong.” It helps a real person recover, and it helps your team find the root cause fast.

For users, an error needs three things: what happened (in plain words), what to do next (a clear step), and whether their data is safe. “Your card was declined. Try a different card or call your bank. No charge was made” is calming and actionable. “Payment failed: 402” is not.

For your team, the same error should carry stable identifiers and useful context. That usually means a small set of error codes you can rely on across endpoints, plus consistent fields so logging, alerts, and UI handling don’t break when one endpoint changes. When a user reports an issue, support should be able to grab an error ID from the UI and an engineer should be able to find the exact trace.

What must never reach the UI

Some details are useful for debugging but unsafe (or just confusing) for users. Keep these out of user-facing messages:

- Secrets (API keys, tokens, passwords, connection strings)

- Stack traces and internal file paths

- Raw SQL, query parameters, and full request payloads

- Names of internal services and infrastructure

- Detailed validation rules that help attackers guess inputs

A simple rule: return safe, user-friendly messages, and keep the sharp details in logs tied to a stable code and a request ID.

Choose a few UI states you will support everywhere

If every screen invents its own error behavior, users feel lost. Agree on a small set of UI states that every page, modal, and form can use, then map API errors to those states the same way every time.

For most apps, a short shared vocabulary is enough: loading, success, empty, needs action (the user must change something), try again (temporary problem), and blocked (they can’t continue without support or a different plan).

Define what each state means in plain words. For example, “empty” means the request worked but there’s nothing to show, while “try again” means the request failed and a retry could work.

Decide what is retryable vs not retryable. A timeout, rate limit, or server overload is often retryable. Missing permission, invalid input, or an expired account usually isn’t retryable until something changes.

A quick rule set helps:

- Try again: temporary, safe to retry

- Needs action: the user can fix it (edit, sign in, confirm email)

- Blocked: the user can’t fix it alone

Also plan for partial success. This happens when a bulk action saves 8 items and 2 fail. The UI should still show what succeeded, then clearly point out what needs action and let the user retry only the failed items.

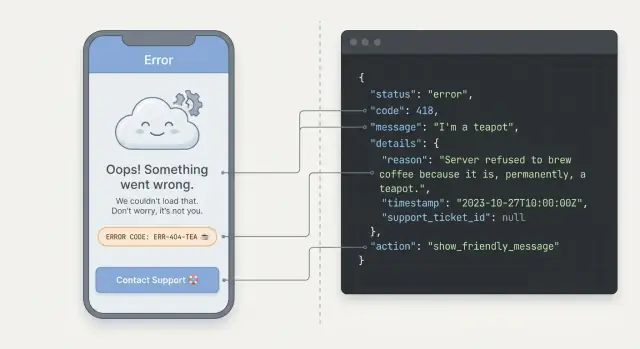

Design a consistent error shape (one format for all endpoints)

If every endpoint returns errors differently, your UI has to guess what happened. A single, predictable error shape is one of the most practical API error handling best practices because it lets you build one set of UI rules and reuse it everywhere.

A simple JSON format

Pick one JSON structure and return it for all failures (validation, auth, rate limits, server bugs). Keep it small, but leave room for details.

{

"error": {

"code": "AUTH_INVALID_CREDENTIALS",

"message": "Email or password is incorrect.",

"details": {

"fields": {

"email": "Not a valid email address"

}

},

"developerMessage": "User not found for email: [email protected]"

},

"requestId": "req_01HZX..."

}

Use stable error codes, and don’t treat message text as a contract. The UI should map codes to the right state, while the message stays human-friendly.

It often helps to keep two messages: a user message that is safe to show, and an optional developer message that helps debugging but still shouldn’t expose secrets.

For forms, reserve a clear place for field errors so you can highlight specific inputs without parsing text.

A few rules that prevent chaos later:

- Always include

error.codeandrequestId. - Keep

error.messagesafe and plain. - Put field-level issues under

details.fields. - Keep codes stable even if wording changes.

- Never leak stack traces or credentials.

Safe error messages users can understand

Good errors help people recover. Bad errors make them retry the same thing or abandon the flow. Be specific about what the user can do next, without revealing how your system works internally.

A safe message explains the outcome and the next step, without leaking details like table names, stack traces, vendor responses, secret keys, or whether an email address exists in your system.

Keep two messages: one for users, one for developers. The user message should be short and calm. The internal one can include the technical reason, the failing service, and a full trace (but only in logs, not in the API response shown to end users).

Patterns that work well:

- Say what happened in plain words: “We couldn’t save your changes.”

- Say what to do next: “Try again in a minute” or “Check the highlighted fields.”

- Avoid blame and jargon: skip “invalid payload” and “unauthorized.”

- Use the same tone everywhere so errors feel familiar, not scary.

Error codes can help, but treat them like support handles, not puzzles. If it helps support, show a short stable code (for example, “Error: AUTH-102”) and keep it consistent over time.

Example: signup fails because the database times out. A safe user message is: “We couldn’t create your account right now. Please try again.” Your internal logs can record: “DB timeout on users_insert, requestId=...”.

If you inherited an AI-generated backend, this separation is often missing. FixMyMess commonly sees raw exceptions returned to users. One of the first fixes is moving the technical detail into logs while keeping the UI message clear and consistent.

Map server errors to UI states (a simple table that works)

Users don’t think in status codes. They think in outcomes: “I can fix this,” “I need to sign in again,” or “Something is down.” Pick a small set of UI states and map every failure to one of them.

A simple mapping you can reuse

Use the same mapping across web, mobile, and admin tools so behavior stays consistent.

| What happened | Typical code | UI state | What the UI should do |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bad request (your app sent something wrong) | 400 | Fixable input | Highlight the field or show a clear message. Don’t suggest retry. |

| Not logged in / session expired | 401 | Re-auth required | Send to login, keep the user’s work if possible. |

| Logged in but not allowed | 403 | No permission | Explain access is blocked, offer “contact admin” or switch account. |

| Not found | 404 | Missing resource | Show “not found” and offer navigation back. |

| Conflict (already exists, version mismatch) | 409 | Resolve conflict | Offer refresh, rename, or “try again” after syncing. |

| Validation failed | 422 | Fixable input | Show per-field messages and keep the form state. |

| Rate limited | 429 | Wait and retry | Tell them to wait, disable the button briefly, then retry. |

| Server bug / outage | 500 | Temporary failure | Apologize, allow retry, and show a support option. |

Network failures and timeouts are separate from server responses. Treat them as “offline/unstable connection”: keep the user on the same screen, show a retry button, and avoid claiming “your password is wrong” when the request never completed.

One practical rule: if the user can fix it, keep them in context (form stays filled). If they can’t, switch to a safe state (re-login, read-only, or contact support).

Step by step: implement consistent errors without a full rewrite

You don’t need to rebuild your whole API to get better errors. Add a thin, consistent layer around what you already have.

Start by deciding on a small set of error codes you’ll support everywhere. Keep definitions short and clear so both backend and frontend teams use them the same way.

Implement the change in one place on each side:

- Pick 8-15 error codes (like

AUTH_REQUIRED,INVALID_INPUT,NOT_FOUND,RATE_LIMITED,CONFLICT,INTERNAL). Write what each means and what the user should see. - Add one server-side error formatter (middleware/filter) that returns the same JSON shape for every endpoint, even when the exception is unexpected.

- Add one client-side error handler that reads that shape and maps it to your UI states (inline field error, banner, toast, full-page error).

- Migrate gradually: update the most-used flows first (login, signup, checkout, save). Leave the rest until you touch them.

- Lock the shape with a few tests so future changes don’t break clients.

A practical migration approach is to support both formats briefly: if an endpoint already returns custom error JSON, pass it through. Otherwise, wrap it in the new format. That keeps risk low.

Example: fix login first. The server stops returning raw stack traces and returns a stable error code with a safe message. The client sees INVALID_CREDENTIALS and shows an inline message near the password field. If it sees INTERNAL, it shows a generic banner and offers a retry.

This is especially helpful in AI-generated codebases where each endpoint throws errors differently. One central formatter and one central mapper can make the app feel consistent fast.

Common flows and how to present errors in the UI

People don’t experience “an API error.” They experience a form that won’t submit, a session that expires, or a payment that doesn’t go through. If your UI treats every failure the same, users guess, retry blindly, or leave.

Forms: validation should feel local

When the server says an input is invalid, show the message next to that exact field. A top-of-page banner like “Something went wrong” makes users scan and retype.

Good patterns:

- Highlight the field, keep the user’s typed values, and focus the first invalid input.

- Use plain language like “Password must be at least 12 characters” instead of codes.

- If there’s also a general error (for example, “Email already in use”), show it near the submit button.

Auth: be clear about what the user can do

For expired sessions, decide one rule and stick to it. If you can safely refresh in the background, do it silently once and continue. If you can’t (refresh fails or it’s a sensitive action), show a clear prompt: “Please log in again to continue.” Avoid dropping users on a blank error screen.

Payments and conflicts need extra care. Say what happened and what action is safe: “Your card was not charged. Please try again.” For conflicts (someone else changed data), explain the next step: “This item was updated elsewhere. Refresh to see the latest version.”

File uploads should answer one question: what made it, and what didn’t? Show progress, keep the successful files listed, and offer a simple retry for the failed ones. If a retry could create duplicates, say that before the user clicks.

Example scenario: a login error handled the right way

A user opens your app after a few days away and tries to sign in. Their saved session token is expired, so the server can’t accept it anymore. That’s normal, but the experience depends on how you report it.

Here is a simple response that follows common best practices and stays safe:

{

"error": {

"code": "AUTH_TOKEN_EXPIRED",

"message": "Your session expired. Please sign in again.",

"requestId": "req_7f3a1c9b2d"

}

}

Use a clear HTTP status (often 401 Unauthorized for an expired or missing token). The code stays stable for the UI and support. The message is written for a human and doesn’t expose details like which part of auth failed or what library you use.

On the UI side, show one calm next step: “Your session expired. Sign in again.” Add a single button that returns them to the login screen. Don’t show stack traces, raw JSON, or scary words like “invalid signature.” If the user was editing something, keep their work in place and only re-auth when they submit again.

For support, display a small help detail or a copy button with the requestId (or error code). That gives your team something actionable: “Please share requestId req_7f3a1c9b2d,” which they can match to logs.

Logging and monitoring that match your error codes

If your API returns a clear error code but your logs don’t, you lose the main benefit. The simplest rule is to log the same error.code you send to the client, every time.

A good log entry is small but complete. Capture enough to debug without dumping sensitive data:

error.codeand HTTP status (example:AUTH_INVALID_PASSWORD, 401)requestId(correlation ID) so you can follow one request end to end- safe user context (userId, not email or tokens)

- the screen or action (route name, endpoint, method)

- internal details for developers (stack trace, upstream error), kept server-side only

Generate a requestId at the edge (or accept one from the client) and return it in the response. When an error blocks a user, show a short message plus “Reference ID: X” so support can find the exact log quickly.

Monitoring is mostly counting and grouping, but it should match how the UI works. Track errors by code and by screen so you can spot patterns like “PAYMENT_DECLINED is mostly on checkout” or “RATE_LIMITED spiked after a release.”

Decide ahead of time what you’ll alert on so notifications don’t turn into noise:

- sudden spikes in 500 errors (server failures)

- repeated auth failures (could be a bug, could be abuse)

- rate limit errors increasing (capacity or client bug)

- one error code dominating a single endpoint or screen

Teams fixing AI-generated backends often find mismatched codes and missing request IDs. Cleaning that up first makes every later fix faster.

Common mistakes and traps to avoid

A lot of bad UX comes from small inconsistencies. Even if each endpoint is “correct” on its own, the product feels random when errors are messy or unsafe.

Common traps:

- Returning different error shapes from different endpoints. The frontend becomes a pile of special cases (

messagehere,errorthere,errors[0]somewhere else). - Using message text as a “code.” It works until someone edits wording for clarity, tone, or translation, then your UI logic breaks.

- Leaking stack traces, SQL snippets, internal IDs, or secret values. Users can’t act on them, and attackers can.

- Treating every error as a toast that says “Something went wrong.” If the user can fix it, tell them how. If they can’t, tell them what to do next.

- Retrying unsafe actions automatically. Retrying a safe read is usually fine. Retrying a write can create duplicates or double charges.

Teams often run into these issues with AI-generated backends. At FixMyMess, we frequently see endpoints that return several formats and accidentally expose secrets in error output.

Quick checklist before you ship

Run this right before release. It catches the small gaps that turn into angry tickets.

API output checks

Confirm every endpoint speaks the same “error language.” Even if the cause differs, the response should look familiar to the client and be easy to log.

- Does every endpoint return the same top-level error shape (for example:

error.code,error.message,requestId)? - Are error codes stable (won’t change next week) and documented in plain words?

- Is there always a safe user message, plus separate internal detail (in logs) when you need it?

- Does each error include a

requestIdso support can find it fast?

UI behavior checks

Make sure the app reacts consistently. Users remember patterns.

- Does the client map server errors to a small set of UI states (validation, auth required, not found, conflict, retry later)?

- Does each message avoid internal details (stack traces, SQL, provider names) and give one clear next step?

- When an error is actionable, does the UI point to the field or step that needs fixing?

- When it’s not actionable (server down, timeout), does the UI say it’s on your side and offer retry?

If your project is an AI-generated prototype, these basics are often missing or inconsistent across endpoints. FixMyMess can audit the code and help make error handling predictable without rewriting everything.

Next steps (and when to get help fixing the code)

Pick one critical flow and make it your “gold standard” first. Login, checkout, or onboarding are good picks because they touch auth, validation, and third-party calls.

Before you change anything, collect about 10 real error examples from production (or from logs and bug reports). Rewrite them to match your new standard: same fields, same naming, same level of detail. That gives you a clear target and prevents endless debates.

A practical path that usually works:

- Add one shared server-side formatter that turns any thrown error into your standard shape.

- Add one shared client-side mapper that turns that shape into the UI states you support (retry, fix input, sign in again, contact support).

- Update just the chosen flow end to end, including tests and a couple of “fake” failures.

- Roll the pattern out endpoint by endpoint instead of trying to fix everything in one release.

- Keep a short set of message rules (what users can see, what must stay internal).

If your app was generated by tools like Lovable, Bolt, v0, Cursor, or Replit, plan extra time. These projects often have inconsistent handlers across routes, duplicate middleware, and raw error objects leaking to the client. The fastest win is usually central formatting and removing one-off responses.

Get help when errors are tied to deeper issues: broken authentication flows, exposed secrets, SQL injection risks, or “it works locally but fails in production” logic. FixMyMess (fixmymess.ai) focuses on diagnosing and repairing AI-generated codebases, including error handling, security hardening, and deployment prep.

If you only do one thing this week, make one flow consistent and measurable. That’s how clearer errors turn into fewer support tickets and calmer users.

FAQ

What should every API error response include?

A good default is a stable error code, a short user-safe message, and a request ID. The code lets the UI react consistently, the message tells the user what to do next, and the request ID lets support find the exact log entry.

Should I rely on HTTP status codes or custom error codes?

Keep HTTP status codes meaningful, but don’t rely on them alone. Use the status for broad categories (auth, validation, server failure) and your own error.code for specific cases so the UI doesn’t have to guess.

How do I make errors feel consistent across the whole app?

Pick a small set of UI states and map every error code to one of them. When the same problem happens on different screens, the app should respond the same way, with the same tone and next step.

How do I write error messages that users actually understand?

Show what happened in plain language, tell the user the next step, and reassure them about safety when it matters (for example, whether they were charged). Avoid jargon like “unauthorized” and avoid blaming the user.

What details should never appear in user-facing errors?

Don’t show stack traces, internal file paths, raw SQL, secrets, tokens, or detailed internal service names. Those details confuse users and can create security risk; keep them in server logs tied to the request ID.

What’s the best way to handle validation errors in forms?

Treat validation as “needs action” and show messages next to the specific fields. Keep the form filled, focus the first invalid field, and avoid generic banners that force users to hunt for what to fix.

How should my app handle expired sessions (401 errors)?

For expired sessions, send a clear prompt to sign in again and try to preserve the user’s work. Use one rule everywhere so users learn what to expect, and don’t show scary technical text like token or signature failures.

How should I handle rate limits (429) and retries?

Default to telling the user to wait briefly and try again, and consider a short cooldown in the UI to prevent rapid repeats. Don’t suggest retry for problems the user must fix, like invalid input or missing permission.

When is it safe to automatically retry a failed request?

Assume retries can create duplicates for writes unless you designed idempotency on purpose. If you can’t guarantee safety, don’t auto-retry; show a clear choice to retry and explain what will happen to avoid double submissions or charges.

How can I improve error handling without rewriting my whole API?

Start by adding one server-side formatter that forces every endpoint into the same error shape, then add one client-side handler that maps codes to UI states. If the backend is AI-generated and inconsistent, FixMyMess can quickly audit and fix leaking exceptions, broken auth flows, and unstable error responses so the app becomes predictable.