Authorization bugs in CRUD apps: audit roles, tenants, routes

Learn how to spot and fix authorization bugs in CRUD apps by auditing role checks, tenant scoping, and API routes before users access others’ data.

Why users end up seeing each other’s data

An authorization bug is when your app lets the wrong person access something even though they’re logged in. That’s different from authentication, which is just proving who someone is (sign in, password, magic link). Authorization answers a different question: now that you’re signed in, what are you allowed to do, and which records are yours?

When authorization is even slightly off, the results are rarely minor. A user might view another customer’s invoices, edit someone else’s profile, or delete records they shouldn’t even know exist. In CRUD apps, this is especially dangerous because everything can look normal in the UI until someone changes a URL, tweaks a request in the browser, or hits an unprotected API route.

This shows up a lot in dashboards, admin panels, and client portals. These apps grow quickly: new screens, new endpoints, new filters. One missing tenant filter in a table query and suddenly records from another account appear.

A common pattern behind these bugs is privilege creep. Permissions quietly expand over time. You start with “users can see their own stuff,” then add support tools, then add an admin view, then add an export endpoint. Each step adds a new place where checks can drift.

A realistic example: a client portal has a “Download receipt” button. The endpoint takes a receipt ID. If the server checks only “user is logged in” but not “receipt belongs to this tenant,” a user can guess or reuse an ID and download someone else’s receipt.

These bugs survive because one of the basics is missing:

- a clear rule for ownership (user, team, or tenant)

- consistent checks on every read and write

- tests that intentionally try cross-account access

Teams often run into this with AI-generated prototypes. Authentication works, but authorization rules aren’t applied consistently across routes and queries. That’s when “it worked in the demo” turns into a production data leak.

Roles, permissions, and tenants - a simple model

Most data leaks happen because the app doesn’t agree on one simple question: who is this user, and what are they allowed to do right now?

Start by naming the identity pieces your app should carry on every request:

- User ID: the person making the request.

- Role: the kind of access they have (viewer, editor, admin).

- Tenant ID: the organization/workspace/project they belong to.

A role check answers, “Can you do this action?” Tenant scoping answers, “Which records are you allowed to act on?” You usually need both.

For example, role = editor might allow “edit invoices.” But without tenant scoping, a query like “update invoice by id” can update an invoice in another workspace. The user had permission, just not for that tenant.

Role checks vs tenant scoping

Role checks are usually simple: can this user delete, can they invite teammates, can they access a billing screen. Tenant scoping is the guardrail that keeps every read and write inside the right org/workspace.

A quick way to remember it:

- Role decides what you can do.

- Tenant decides where you can do it.

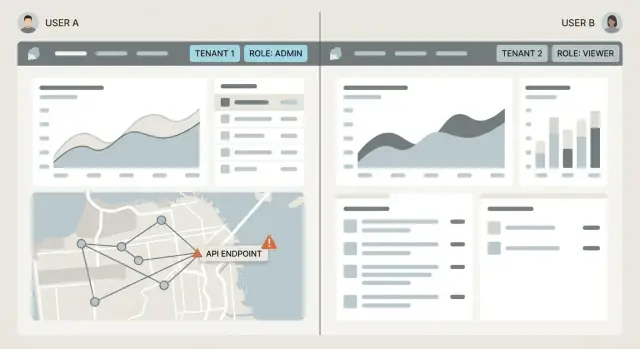

The “admin” trap

“Admin” is where many apps get sloppy. There’s a big difference between:

- Tenant admin: can manage users and settings inside their own workspace.

- Global admin: can access everything across all tenants (rare, usually internal staff).

If your code treats any admin as global, a normal customer admin can end up seeing other customers’ data. This is especially common when “admin” is implemented as a single flag without clarifying scope.

One more warning: UI-only restrictions aren’t security. Hiding buttons helps usability, but it doesn’t protect data. If an API route accepts a request, a user can still call it directly, even if the UI never shows the option.

Where authorization should be enforced

Authorization isn’t one check you add “somewhere in the backend.” In most leaks, a team did have a check, but it lived in the wrong place or only covered one layer.

Think of enforcement as a stack. Each layer blocks a different kind of mistake, especially in fast-built code where handlers get copied and edited.

Think in layers (not a single guard)

Start at the edge, where requests enter your system. If an endpoint shouldn’t be callable by a role, block it before any work happens. That prevents “I can hit the URL directly” issues.

Next, enforce access to the specific record. It’s not enough to know someone is logged in. You must prove the record belongs to their tenant (or that they have a valid cross-tenant reason, like an internal support role).

Finally, control what they can see or change inside that record. Many apps limit which rows are returned but still leak sensitive fields (internal notes) or accept edits to server-owned fields (role, plan, tenantId).

A practical way to place checks:

- Route access: who is allowed to call this endpoint at all

- Record access: which specific item(s) they can read or modify

- Action access: what they can do (read vs edit vs delete vs export)

- Field access: which properties are returned or accepted

A rule that catches most leaks

Assume clients are untrusted, even your own frontend. If a request includes an ID, a tenantId, or a role, treat it as a hint, not a fact. The server should derive identity and tenant from the session or token, then apply that to every query and write.

When reviewing code, look for places where only one layer exists. If any route returns data, ask: did we enforce access at the route, record, action, and field level, or did we only do one of them and hope it covers the rest?

Start with a permission map you can actually follow

Most authorization bugs start as a paperwork problem. Nobody can answer, in one place, “Who is allowed to do what, to which records?” So checks get added ad hoc, routes drift, and privilege slowly creeps.

A permission map is a plain-language reference you can keep open while auditing routes and queries. Keep it small enough that a non-technical teammate could read it and spot a weird rule.

1) Write the roles-to-actions table (no code words)

Start with the roles you actually have in production, not the ones you plan to have. Then map them to actions using simple verbs: view, create, edit, delete, invite, export, change billing.

| Role | Can view | Can create | Can edit | Can delete | Can manage users |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Member | Own items | Yes | Own items | No | No |

| Manager | Org items | Yes | Org items | Limited | Invite members |

| Admin | Org items | Yes | Org items | Yes | Full |

If you can’t describe a rule without exceptions, that’s a sign you need one more role or one more concept like “owner.”

2) Mark every tenant boundary and the key that scopes it

Many apps have more than one boundary: account, org, workspace, project. Write each one down and choose the scoping key for it (for example, org_id or workspace_id). Then list each resource and the tenant key that must always be present.

When you do this, focus on three questions:

- What scopes each resource (org_id, workspace_id, project_id)?

- Where does that scope come from (session, token, URL, request body)?

- Which boundaries are never allowed to cross?

Finally, define “owner” per resource. Owner isn’t universal. A comment might be owned by its creator, a task by its assignee, an invoice by the account.

A concrete example: if “owner” for a document means “creator,” then a manager shouldn’t automatically edit every document unless your table says managers can edit all org documents. This one detail prevents a common mistake: using role checks to skip tenant scoping.

Step-by-step audit: API routes and server handlers

Authorization bugs often hide in boring places: the routes you forgot existed, the handler that “just updates a record,” or the admin endpoint that never got real checks. An audit is mostly inventory plus discipline.

1) Inventory every route (yes, all of them)

List every API route your app exposes, including internal, admin, and “temporary” endpoints added during prototyping. These experiments often stick around and stay reachable.

Pick one source of truth (your router file, framework route folder, or API gateway config) and create a simple table. If you find routes that aren’t used anymore, mark them for removal, but audit them first.

2) For each route, write: actor, action, resource, tenant boundary

For every route, write one sentence in plain English:

- Actor: who is calling this (logged-in user, org admin, system job)?

- Action: what are they doing (read, create, update, delete)?

- Resource: what object is touched (invoice, project, user, file)?

- Tenant boundary: what container must match (org_id, workspace_id, account_id)?

If you can’t describe the rule in one sentence, the code is usually inconsistent.

3) Verify tenant scope on the server, not the client

Check that the handler derives tenant from the authenticated session (or server-side token claims), not from request body fields or query params.

A common red flag: the request includes orgId and the server trusts it. A safer pattern is: read org_id from the user session, then enforce it in every query and mutation.

4) Confirm writes are scoped too (not just reads)

Teams often scope list pages but forget updates and deletes. Look for endpoints like:

PATCH /projects/:idDELETE /invoices/:idPOST /members/:id/role

If the handler updates by id only, it’s an instant cross-tenant risk. The check must be: “record with this id AND this tenant belongs to this actor.”

5) Watch routes that accept IDs and fetch records “naked”

Any route that takes an id is a hotspot. The dangerous pattern is:

- fetch by

id - check something loosely (or not at all)

- return or mutate

Instead, enforce authorization as part of the lookup. If the record isn’t in the actor’s tenant (or the actor lacks permission), the lookup should fail.

Step-by-step audit: database queries and ORM filters

Authorization can look fine in the controller, then quietly break in the database layer. If a query can return records from another tenant, the app will eventually show them, maybe in search, exports, or edge cases you didn’t test.

Start by finding every place your app reads “many rows” (list pages, search, admin tables, background jobs). For each query, ask one question: where is the tenant filter applied, and can it be skipped?

1) Audit list queries (many rows)

Open each list endpoint and trace it down to the ORM call. Tenant constraints must be part of the query every time, not added later in memory.

A checklist that catches most leaks:

- Tenant scope is in the database query (not filtered after fetching).

- Pagination uses the same scoped query (count and data queries match).

- Search terms are combined with tenant scope using AND, not OR.

- Sort and cursor logic can’t fall back to an unscoped base query.

- “Include related data” doesn’t load cross-tenant children.

2) Audit detail queries (single row)

Detail endpoints should never look up by record id alone. The lookup must include tenantId and id (or another tenant-bound unique key). If your ORM has helpers like findUnique(id), treat them as suspicious unless the unique key includes tenantId.

Prefer “find first where tenantId = X and id = Y” over “find by id then check tenant later.” The second pattern is easy to forget in one handler.

3) Joins, exports, and “special” queries

Joins are a common place where tenant scoping disappears. A query might start scoped, then join to another table and filter on the wrong tenant field (or not filter at all).

Also check reports, exports, and background jobs. These often bypass the normal API route code, so they need the same scoping rules at the query level.

Common traps that cause privilege creep

Privilege creep usually doesn’t happen because someone writes “allow all.” It happens because small shortcuts add up: one route trusts the UI, another assumes “admin” means global, a third forgets about a background task.

Mistake 1: Trusting the client (UI flags, hidden buttons)

If a user can edit a request, they can edit anything the browser sends. A hidden “Delete” button or a client-side role: "admin" flag isn’t protection. The server must decide based on the logged-in identity.

A common version: the UI hides “Edit invoice” unless you are a manager, but the API route only checks that you’re signed in. Anyone can call the route directly and update someone else’s invoice.

Mistake 2: Using “isAdmin” without tenant scope

“Admin” is meaningless unless you say: admin of what? In multi-tenant apps, most roles should be scoped to a tenant. The trap is writing logic like “if isAdmin, allow,” and accidentally granting access across all tenants.

A safer mental check: every authorization decision should answer two questions, “who is this user?” and “which tenant does this data belong to?” If either answer is fuzzy, you’re one refactor away from cross-tenant access.

Mistake 3: Checking after loading the record

Many leaks happen because code fetches a record first, then checks if the user is allowed to see it. Even if you block the response, you can still leak through error messages (different 404 vs 403), timing differences, or related data loaded along the way.

Prefer checks that prevent the record from being fetched at all by including tenant and ownership rules directly in the query.

Mistake 4: Forgetting “side doors” (jobs, webhooks, downloads)

Background jobs, cron tasks, webhook handlers, and file download endpoints often skip the usual middleware and end up with weaker checks. If a job processes “all invoices” without a tenant filter, it can email or export the wrong customer data.

For these paths, make sure you can answer: does it authenticate the caller (or validate the webhook), enforce tenant scoping on every query, and log what it touched (tenant id, record id, actor)?

Mistake 5: Shared helpers with unclear defaults

A helper like getUserProjects(userId) sounds safe until someone reuses it in an admin screen and assumes it returns “all projects.” Or worse, a helper defaults to “no tenant filter” when tenantId is missing.

Good helpers fail loudly. If tenantId is required for safety, make it required in the function signature and throw if it’s missing.

A realistic example: one bad route, one big leak

Imagine you have a Support Agent role. They should be able to view support tickets, but only for their own organization (their tenant). That sounds simple, but it only takes one careless endpoint to break the rule.

Here’s the mistake: the API has a route like GET /api/tickets/:ticketId. The handler checks that the user is logged in, then fetches the ticket by ID. It never checks the tenant.

// Unsafe: fetches by ID only

const ticket = await db.ticket.findUnique({

where: { id: ticketId }

});

return ticket;

Why this leaks data: ticket IDs often show up in places users can access, like browser URLs, email notifications, logs in support tools, or exported CSVs. Even without that, many apps use predictable IDs (incrementing numbers, short UUIDs copied from the UI). A curious or malicious user can swap one ID for another and see a ticket from a different org.

That’s one of the most common failures: the code assumes that knowing an ID is proof you should see the record.

A safer handler does two things differently:

- Scopes the query to the tenant (org) from the session.

- Checks the role for the action (viewing a ticket).

// Safer: enforce role + tenant scoping

if (user.role !== "support_agent") throw new Error("Forbidden");

const ticket = await db.ticket.findFirst({

where: { id: ticketId, orgId: user.orgId }

});

if (!ticket) throw new Error("Not found");

return ticket;

Notice the “Not found” behavior. It avoids confirming that a ticket exists in another org.

To verify the fix, keep the test simple:

- Create two orgs, Org A and Org B.

- Create a ticket in Org B.

- Log in as a Support Agent in Org A.

- Call the endpoint using Org B’s

ticketId. - Confirm you get “Not found” (or 404), and no ticket data is returned.

Quick checks you can run before a release

Most authorization bugs show up in the last mile: a new route, a “helpful” admin shortcut, or a query that forgot tenant scoping. These checks are simple and repeatable.

The two-account smoke test (10 minutes)

Create two test accounts that look normal but belong to different tenants (Company A and Company B). Give them realistic data so you can tell what belongs where.

Then intentionally mix identifiers:

- Copy a record ID from Tenant A and try to read it from Tenant B.

- Try an update with Tenant A’s ID while logged in as Tenant B.

- Try a delete with Tenant A’s ID while logged in as Tenant B.

- If your app uses soft delete, test restore/undelete too.

- Repeat for child objects (comments, invoices, files) that may be scoped differently.

If any of these succeed or return real data, you likely have missing tenant filters or a role check that only runs in the UI.

Don’t forget bulk and side-door features

Leaks often happen outside the main CRUD screens. A list endpoint may be scoped, but export isn’t. A file download may skip checks because it’s “just a URL.”

Do a quick pass over:

- List pages with filters, search, sorting, and pagination (try searching for a known value from the other tenant).

- Export endpoints (CSV, PDF, reports) and background jobs that generate them.

- File downloads and previews (signed URLs, attachment IDs, image endpoints).

- Activity logs, admin dashboards, and “recent items” widgets.

- Any route that accepts an ID in the path, even if the UI never exposes it.

Also confirm your admin roles are scoped the way you intend. “Tenant admin” shouldn’t act like “global admin” just because it’s convenient.

Next steps: make authorization hard to break

Authorization failures rarely happen because people don’t care. They happen because checks are scattered, tenant filters are easy to forget, and new features ship faster than the rules get updated. The goal is to make the safe path the easiest path.

Put one guardrail in front of everything

Use one consistent authorization layer everywhere: middleware, a policy helper, or a service function that every handler calls before doing work. If you have to remember which routes “need checks,” you’ll miss one.

A useful rule of thumb: route handlers shouldn’t contain custom permission logic. They should ask a policy layer a clear question (for example, “Can this user update this invoice?”) and then proceed.

Changes that reduce mistakes quickly:

- Create one policy helper (or middleware) per resource: read, create, update, delete.

- Make tenant scoping the default (for example, a scoped query helper that always applies tenantId).

- Deny by default when data is missing or ambiguous (no tenant, no role, no ownership).

- Log authorization denials with enough context to debug (user, tenant, resource, action).

Bake tenant scoping into data access

Centralize tenant scoping so it’s hard to forget. The best place is where queries are built, not where responses are returned.

For example, instead of writing where: { id } in many places, expose a helper that already includes tenantId. If a developer tries to bypass it, it should look wrong in code review.

High-value tests catch the regressions that matter most:

- Cross-tenant read fails (User A can’t fetch User B’s record by ID).

- Cross-tenant write fails (User A can’t update/delete User B’s record).

- Role downgrade is safe (a user losing admin rights can’t keep admin access).

- Create is scoped (new records are stamped with the current tenant).

If you’ve inherited an AI-generated codebase and you’re not confident tenant scoping and role checks are enforced consistently, a focused audit can save days of guesswork. FixMyMess (fixmymess.ai) specializes in diagnosing and repairing these kinds of authorization gaps, especially the “id-only” handlers and unscoped queries that look fine until real users hit production.

FAQ

Why can users see someone else’s data even though login works?

It’s an authorization problem, not an authentication problem. They can be fully logged in, but your server isn’t consistently proving that the record they’re requesting belongs to their user/team/tenant before returning it.

What’s the difference between authentication and authorization?

Authentication answers “who are you?” Authorization answers “what are you allowed to do, and which records are yours?” Most cross-account leaks happen when apps only check that a user is signed in, then fetch data by ID without checking ownership or tenant scope.

Do I need role checks, tenant scoping, or both?

Role checks decide what actions a user can take, like “can edit invoices.” Tenant scoping decides where they can take those actions, like “only inside this workspace.” You usually need both, because a user can have the right role but still target the wrong tenant’s records.

Which endpoints are most likely to leak cross-tenant data?

Any endpoint that accepts an ID is a hotspot, especially download, export, and “detail” routes. If the handler fetches a record by id alone, a user can swap IDs and potentially access another tenant’s data.

If the UI hides admin features, is that enough security?

No. Hiding buttons only improves the UI; it does not protect the API. Assume anyone can call your endpoints directly, so the server must enforce permissions and tenant ownership on every read and write.

What’s the “admin trap” and how do I avoid it?

“Admin” needs scope. A tenant admin should only manage things inside their own tenant, while a global admin can see everything and should be rare and tightly controlled. If your code treats any admin as global, you can accidentally grant cross-tenant access.

Why is it risky to load a record first and check access afterward?

Because it’s easy to forget one handler, and you can still leak information through side effects like error differences, timing, or related data loading. The safer pattern is to include tenant and ownership rules directly in the database lookup, so unauthorized records are never fetched.

Should the server trust tenantId or role sent from the client?

Derive identity and tenant from the server-side session or token claims, then apply them to every query and mutation. Treat any tenantId, role, or userId coming from the client as a hint at best, not something to trust.

What’s the fastest way to smoke test for authorization leaks?

Create two accounts in two different tenants with clearly different data. While logged in as Tenant B, try to read, update, and delete records from Tenant A by reusing IDs; if anything succeeds or returns real data, you have a scoping gap that needs fixing before release.

Why do AI-generated CRUD apps have so many authorization bugs, and what can I do?

AI-built prototypes often get authentication working quickly but apply authorization inconsistently across routes and queries, especially in copied handlers and “temporary” endpoints. If you inherited a codebase like that and want it production-safe fast, FixMyMess can run a focused audit and repair the id-only handlers, unscoped queries, and role/tenant mistakes, often within 48–72 hours after a free code audit.