Exposed secrets in AI-generated code: find and rotate keys

Exposed secrets in AI-generated code can leak via repos, logs, and env files. Learn how to find them, rotate credentials, and harden access.

What counts as a secret (and why it becomes urgent)

A secret is anything that proves your app is allowed to access something. If it leaks, an attacker often doesn’t need to break in - they can just authenticate as your app.

Secrets include API keys, database usernames and passwords, OAuth client secrets and refresh tokens, JWT signing keys, private keys (SSH, TLS), webhook signing secrets, and cloud service account keys. A simple rule: if a value would let someone read data, write data, deploy code, or spend money, treat it as a secret.

AI-generated prototypes often hardcode secrets because speed wins early on. Prompts produce copy-paste snippets with “temporary” keys, and people paste credentials into config files to get a demo working. The app works, so the shortcut stays.

Once a secret is exposed, assume it’s already compromised. The typical fallout looks like:

- Silent data access (customer records, internal docs, backups)

- Surprise bills (AI APIs, cloud compute, email/SMS providers)

- Account takeover (admin panels, CI/CD, cloud consoles)

- Long-term persistence (new keys created, permissions widened)

Remediation is more than “change the password.” It’s three connected tasks:

- Discovery: find every place the secret exists, including copies.

- Rotation: replace it safely without breaking production.

- Prevention: stop the next build from reintroducing it.

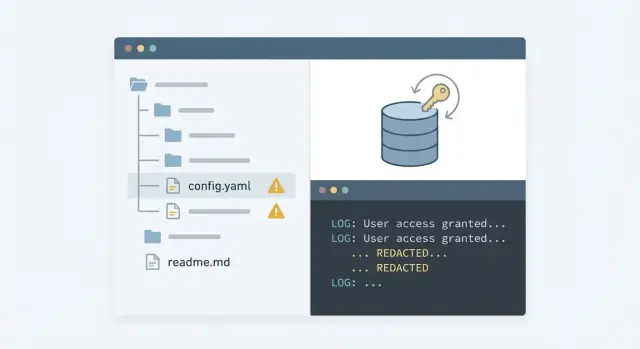

Where keys usually leak in AI-generated projects

AI-generated prototypes tend to grow fast: copied snippets, quick deploys, and “temporary” debug code. That’s why leaks usually show up in several places at once.

The usual leak points

Check these first:

- Public repos and forks: a repo can be public briefly, then made private, and the key still gets copied. Forks and mirrors can keep it alive.

- Git history: deleting a

.envfile or config file isn’t enough. If it was committed once, the secret can still be pulled from old commits. - Logs and debug output: build logs, server logs, and “print the token” debug statements can leak credentials. Error trackers can capture headers too.

- Env files and exports:

.envfiles get committed, bundled into zip exports, or baked into Docker images. Teams also share them in chat when something breaks. - Client-side bundles: anything shipped to the browser should be treated as public. Frontend code sometimes ends up containing keys or privileged endpoints.

A common pattern: someone tests Stripe and Postgres locally, commits a working demo, then “cleans it up” by adding .env to .gitignore. The repo now looks safe, but the first commit still contains the password. The deploy logs might also include the connection string.

If you’re seeing these patterns, treat it as an incident, not a cleanup task.

Quick signs you already have exposed secrets

If your app was generated quickly, assume you might have exposed secrets until you check. These leaks are rarely subtle. They often sit in plain sight in files that got committed during a rush.

Start with a simple search for obvious markers. You’re not trying to prove everything is safe yet. You’re trying to find high-risk hits that need action.

api_key

secret

password

DATABASE_URL

Bearer

BEGIN PRIVATE KEY

If any of those show up next to a real-looking value (long random strings, base64 blobs, JWTs, or full connection URLs), treat it as compromised.

Also look for config files that shouldn’t be committed at all: .env, config.json, serviceAccount.json, and “backup” copies like .env.old or config(copy).json. Templates and generated code often drop credentials into these by default.

Don’t stop at “main” code. Leaks hide in places people forget to review:

- Seed scripts and migration helpers that connect to production “just to populate data once”

- Tests and mocks that include real tokens to “make it pass”

- README notes or commented snippets

- Generated code dumps where entire config folders were pasted in

Check recent commits too. Big warning signs include huge one-shot commits, messages like “working version” or “temp,” or copying a template and editing later. Those are the moments when secrets get baked into history.

Step by step: find leaked secrets without making it worse

When you suspect exposed secrets, the first job is to stop creating new copies while you investigate.

A safe search flow

Pause anything that produces or shares builds: auto-deploys, preview links, demo branches. If someone is about to “just test one more thing,” ask them to wait. Every new run can spread the same key into more places (artifacts, caches, logs).

Then work locally. Pull the repo to your machine and scan without uploading code to third-party tools. Look for API keys, tokens, connection strings, private keys, and lines that include words like SECRET, TOKEN, KEY, PASSWORD, or DATABASE_URL.

Next, search the past, not only what exists today. A secret removed last week can still be sitting in git history and reachable to anyone with repo access. Plan to scan commits and tags, not just the working tree.

After code and history, check places where secrets get printed by accident: CI job output, build logs, server logs, and error reporting. A single debug line can leak a token even if the code looks clean now.

Finally, write everything down before rotating anything. Inventory each secret, where you found it, what it grants access to, who owns it, and what must be updated after rotation.

- Pause deployments and stop sharing preview builds.

- Scan the current repo locally for key-like strings and config values.

- Scan git history (commits, tags) for earlier leaks.

- Review CI and hosting logs, plus error reports, for printed credentials.

- Create a single inventory table mapping secret -> owner -> system -> severity.

If you find a database password in an old commit and the same value in CI logs, treat it as compromised. It helps to separate “found” from “confirmed used” so rotation happens in the right order.

Containment: stop the bleeding in the first hour

Treat the first hour like incident response, not a refactor. The goal is to stop new damage while you figure out what leaked and where it spread.

Disable the highest-risk credentials first. If a cloud root key or an admin database user is exposed, assume someone can do anything with it. Revoke or disable it immediately, even if that causes downtime. A short outage is usually cheaper than a copied database.

Assume secrets may have been copied into places you can’t fully track: build artifacts, error logs, CI output, hosted preview environments. That usually means rotating more than the one key you found.

Fast containment moves that cover many AI-generated projects:

- Revoke or disable cloud root keys, admin DB users, and any “god mode” API keys.

- Put the app in maintenance mode or temporarily block public access while you work.

- Restrict inbound access (lock down database networking, pause webhooks, IP allowlist admin panels).

- Invalidate active sessions if signing keys or JWT secrets were exposed (force logout).

- Freeze deployments so CI doesn’t keep re-leaking secrets into logs.

If an AI tool put a Postgres URL with a password into a repo, treat the password as burned. Also rotate any related connection strings stored in hosting settings, serverless config, background workers, and anywhere else that might share the same credential.

A practical rotation plan (who, what, when, and in what order)

The goal isn’t just to change keys. It’s to change them in a safe order, with clear owners, without locking your app out of its own services.

Start by mapping “who and what” for each secret. Write down:

- Which service uses it (database, auth provider, storage)

- Which environments it touches (dev, staging, prod)

- Which systems and people can read it (teammates, CI, hosting)

Prioritize rotation by blast radius. Rotate secrets with the broadest access first (cloud root keys, admin tokens, CI/CD tokens), then move to narrower, app-specific keys (a single database user, one webhook secret). Broad keys can be used to mint more access, so they’re the most urgent.

A simple rotation sequence for each secret:

- Create a replacement secret (new key, new database user, new token) with the minimum permissions needed.

- Update config in the right place (secret manager, CI variables, runtime env), and remove any copies from code and env files.

- Deploy and verify critical paths (login, payments, background jobs) using the new secret.

- Revoke the old secret and confirm it can no longer authenticate.

- Record what changed, where it’s stored now, and who can read it.

Pick a rotation window based on impact. For production databases, plan a short maintenance window or use a dual-credential overlap (new works before old is revoked). Define a rollback plan that rolls forward by fixing config, not by restoring the leaked key.

Rotating database credentials the safe way

Database credential rotation feels simple, but it’s easy to break production if you do it in the wrong order. The goal is a clean cutover with minimal downtime.

Create a fresh database user for each app or service. Avoid one shared “admin” login used by everything. If one service leaks, the blast radius stays small.

Give the new user only what the app needs. Most apps don’t need to create databases, manage roles, or read internal system tables.

A safe sequence:

- Create a new DB user and apply least-privilege grants.

- Update the connection string in one environment (usually staging first), then deploy and verify key flows.

- Repeat for production, then for dev (dev leaks are still leaks).

- Search for hardcoded credentials in scripts, migrations, seed files, CI configs, and backups before calling it done.

- Disable the old user and confirm it can’t reconnect.

When you cut over, verify with real actions: sign-in, create a record, run a background job, and confirm errors aren’t being swallowed. Also check pooled connections. Some apps keep old connections alive for minutes or hours, which can hide problems until later.

Finally, remove the old credentials everywhere they might still exist: cron jobs, one-off admin scripts, copied .env files, and “temporary” backups.

Access hardening after rotation (so it does not repeat)

Rotating keys fixes today’s problem. Hardening stops the next leak. The goal is straightforward: secrets live outside the repo, are limited to the minimum needed, and are easy to audit.

Move secrets out of code. Use environment variables for simple setups, or a secret manager if you have multiple services. Treat .env files as local-only: keep them out of source control, don’t copy them into images, and don’t print them in startup logs.

Reduce blast radius. Don’t reuse one “master” key everywhere. Split by environment (dev, staging, production) and by service (web app, background worker, analytics). If one key leaks, you rotate a small piece, not your whole stack.

Lock down access in CI and hosting

CI and hosting are common leak points because they touch every build. Tighten permissions so only the right job, on the right branch, can read production secrets.

- Use separate CI credentials for read vs deploy, with the smallest scopes possible.

- Restrict who can view or edit secrets in CI and your hosting provider.

- Limit deployments to protected branches.

- Turn on audit logs and review them after rotations.

- Mask secrets in logs and disable verbose debug output in production.

If you’re inheriting an AI-built prototype, explicitly look for “helpful” debug prints. It’s common to see apps dumping full config objects or database URLs on failure.

Add guardrails in your repo

Hardening should be automatic, not a promise.

- Add pre-commit secret scanning and block commits that match key patterns.

- Require code review for changes that touch config, auth, or deployment files.

- Protect main and release branches, and require status checks.

- Set a rule: no secrets in examples, tests, or seed scripts.

A common failure mode: someone rotates a leaked database password, but leaves the same value in a test script used by CI. A later build fails and prints it. Guardrails prevent that second leak.

Common mistakes that keep secrets exposed

Most leaks stick around because the fix is only half-done. With AI-generated code, it’s common to patch the visible problem and miss places where the same key is still usable.

One frequent mistake is rotating a credential but not disabling the old one. If the previous key still works, anyone who copied it from a commit, a build log, or a screenshot can keep using it. Rotation should include revocation or expiry, not just creating a new value.

Another trap is scanning only the current branch. If a secret was committed even once, removing it from the latest version doesn’t remove it from earlier commits.

Watch for patterns that reintroduce leaks:

- Putting API keys or database URLs in frontend code because it works in a prototype

- Reusing one mega-admin key everywhere (prod, staging, local dev)

- Logging full error objects that include headers, tokens, or connection strings

- Leaving

.envfiles in places that get copied into images or shared folders - Rotating only the database password but forgetting app-level tokens that still grant access

A simple rule: treat every secret as compromised until you can prove (1) it’s revoked, (2) it’s removed from history and logs, and (3) access is reduced to the minimum needed.

Quick checklist before you redeploy

Treat this as a gate. If any item fails, pause the deploy. Redeploying with the same leak turns a mistake into an incident.

The surprise is often that the key is gone from the latest commit but still lives in git history, a pasted stack trace, or a build artifact you forgot to delete.

A fast pre-deploy checklist that catches many repeat failures:

- Confirm the repo is clean: scan current files and git history, and remove packaged artifacts (zips, build folders, debug dumps) that may contain keys.

- Verify every environment is updated: local dev, preview/staging, production, CI, and background jobs all use the newly rotated values.

- Prove old credentials are dead: revoke them at the source (database, cloud, third-party), then test that they can’t authenticate.

- Re-check permissions: new database users and API tokens should have only the access they need (read vs write, limited schema/tables, no admin by default).

- Add tripwires: enable alerts for unusual login attempts, sudden request spikes, or unexpected spend.

Do one reality check before the full rollout: deploy to a non-production environment first and run the flows that touch secrets (login, payments, email, file uploads). If something breaks, fix it there instead of hot patching production.

Example scenario and next steps

A founder ships a quick Lovable prototype and pushes it to a public repo to share with a friend. A week later, someone reports that the app is “acting weird.” In the repo, there’s a committed .env file and a hardcoded DATABASE_URL in a config file. The demo worked, but the safety basics were missing.

Treat it as an active incident. Assume the secret was copied. Capture evidence for later (don’t paste keys into chat), then stop new damage: put the app in maintenance mode, pause background jobs, and block outbound database access if you can.

Then find every leak point, not just the obvious file. Check repo history (older commits often still contain the key), build logs, error logs, and hosted preview environments that may have printed connection strings.

Rotate in a safe order. Create a new database user with least-privilege permissions, update the app’s environment variables, and redeploy. Confirm the app connects using the new user. Only after you see clean traffic, revoke the old database user and invalidate any related tokens.

Write down what happened so it doesn’t rely on memory later:

- Secret inventory: what it is, where it lives, and where it must never appear (repo, logs, tickets)

- Owner: who can rotate it and who approves access

- Rotation date: when it was last changed

- Access rules: which services and IPs can reach the database

- Verification notes: how you confirmed the old secret no longer works

If your project was generated in tools like Replit, Cursor, Bolt, or v0, it’s common to have more than one hidden leak (duplicate configs, sample files, debug prints). If you want a focused diagnosis, FixMyMess (fixmymess.ai) starts with a free code audit to map leak paths and prioritize rotation, then helps repair and harden the codebase so it’s ready for production.