File upload security for prototype apps: practical safeguards

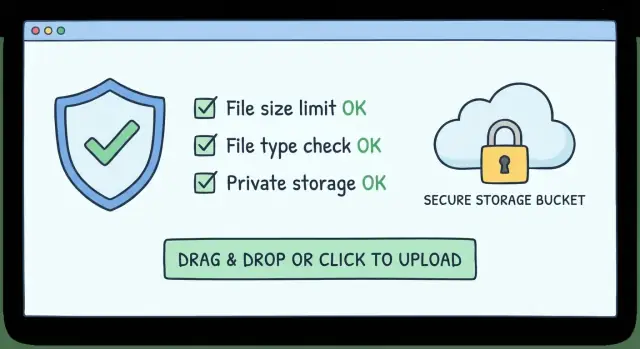

File upload security for prototype apps: set size limits, validate real file types, store uploads privately, scan for malware, and avoid public bucket leaks.

What can go wrong with uploads in a prototype

File uploads are a favorite attack path because they cross a lot of boundaries at once: your app, your storage, and whatever later reads the file. A “simple” upload button can turn into a way to run code in a browser, leak private files, or run up your cloud bill.

Most problems come from prototype shortcuts. Teams trust the filename extension (like .png), skip checks when a file is “small enough,” or upload straight into a shared cloud bucket with broad permissions. Another common shortcut is serving the uploaded file back from the same place it was stored, without thinking through access control or browser behavior.

When uploads are loose, the outcomes are predictable:

- Account takeover (for example, a file that triggers a bug in image/PDF handling)

- Data leaks (a “private” upload ends up public, or users can guess URLs)

- Big cloud bills (large files, repeated retries, or bots abusing your endpoint)

- Brand damage (malware hosted under your domain or bucket)

A simple mental model helps: every upload flow has four steps - accept, validate, store, serve.

- Accept is where you set limits and block obvious abuse.

- Validate is where you confirm what the file really is, not what it claims to be.

- Store is where permissions matter most, because one misconfigured bucket can expose everything.

- Serve is where headers and access checks keep your app from becoming a file hosting service.

Example: your prototype lets users “upload a profile photo.” An attacker uploads avatar.png that’s actually HTML or a script. If you store it in a public bucket and serve it with the wrong Content-Type, it can run in someone else’s browser and steal session data.

Set clear size and rate limits first

Most upload incidents start with “we’ll add limits later.” Limits are some of the simplest controls you can add, and they protect you from surprise bills, slowdowns, and abuse.

Start with what users truly need. If you only need profile photos, a 5-10 MB limit is usually enough. If you accept videos or design files, pick a higher limit on purpose, and expect to add more safeguards.

Don’t rely on a single setting. Put limits in a few places so one misconfig doesn’t undo everything:

- A hard max size per file

- A max total size per request (so 20 “small” files can’t become huge)

- Upload timeouts

- Per-user daily caps (files/day or total MB/day)

- Burst rate limits (uploads/minute)

Timeouts matter more than they get credit for. Without them, an attacker can drip data slowly and tie up your server workers. If you use pre-signed uploads directly to storage, set a short expiry so the URL can’t be reused forever.

Make error messages clear so real users can fix the problem quickly. Say what failed and what the limit is (for example, “File too large. Max 10 MB.”). Keep “too many uploads today” separate from “upload timed out,” because they usually mean different things.

Validate the real file type (not just the name)

A filename like invoice.pdf tells you almost nothing. Anyone can rename invoice.exe to invoice.pdf and upload it. Treat extensions as a hint, not a rule.

Browsers also send a declared MIME type (like image/png). Check it, but don’t trust it. It’s user-controlled data.

Confirm the type from the file’s contents

Use “magic bytes” (the file header) to identify what the file actually is. A real PNG has a specific signature at the start of the file. This catches common tricks where the name and declared MIME say one thing, but the contents are something else.

Keep the decision simple: accept only the exact types you support and reject everything else. An allowlist is safer than trying to block “bad” types.

For many prototypes, a reasonable starting allowlist is image/jpeg, image/png, and application/pdf. Add text/plain only if you have a clear use case, and be careful about rendering it.

Watch out for ZIP and Office formats

ZIP files and Office documents (DOCX/XLSX/PPTX) are higher risk because they’re containers. They can hide scripts, macros, or surprising structures. If you must accept them, treat them as “extra checks required”: tighter limits, malware scanning, and no direct serving.

Concrete example: if someone uploads profile.png but the magic bytes say it’s a Windows executable, reject it immediately and log the attempt.

Handle filenames and paths safely

A lot of upload bugs aren’t about malware. They’re about trusting filenames too much. If your app uses the user-provided name to build a path, a simple upload can overwrite files, break pages, or leak data.

Treat every filename as untrusted input. Users can include path characters, control characters, or confusing Unicode that looks normal on screen but resolves differently on disk.

Safer filename rules

The safest pattern is to ignore the user’s filename for storage. Generate a server-side name (like a random ID or UUID), and keep the original name only as display text in your database after cleaning it.

Practical rules that prevent most filename trouble:

- Generate your own storage name and choose the extension yourself

- Strip path separators (

/,\\), leading dots, and invisible characters - Normalize Unicode so lookalikes don’t create weird duplicates

- Block double extensions (like

photo.jpg.exe)

Example inputs to design against: ../../app.env or avatar.png\u202Egnp.exe. If you save those names directly, you can write outside the intended folder or hide an executable behind a fake-looking name.

Keep uploads out of public paths

Never store user uploads inside your app’s public web folder. Put them in a private location (a private bucket or private disk path), then serve them through a controlled download endpoint.

Also separate raw uploads from processed outputs. Store the original file in one place, and resized images or converted previews in another. It makes permissions easier and cleanup safer.

Store uploads safely with private buckets and tight permissions

The safest default is simple: treat every upload as private until you have a clear reason to make it public. Most “prototype leaks” happen because storage is set to public-read for convenience and never corrected.

Keep user uploads separate from your app’s static assets. Put user content in one bucket (or container) and site assets (logos, CSS, build files) in another. That way a permission mistake on uploads doesn’t expose the whole app, and your build pipeline can’t overwrite user files.

Lock down who can write

Upload through a small server-side service with the least privileges possible. That service should be able to write new objects and read only what it needs. Avoid permissions that allow listing everything, deleting everything, or changing bucket policy.

Aim for a few boring defaults: private objects, separate buckets for dev/staging/prod, encryption enabled where supported, and audit logs on for policy and object access.

Let users download without making files public

When a user needs to download a file, use short-lived signed URLs generated by your server. That gives time-limited access without flipping the object to public.

Keep secrets out of the client. Don’t ship access keys, write permissions, or admin storage tokens in browser code.

Process and serve uploads without exposing users

Uploading a file is only half the risk. The other half is what your app does next: processing, previewing, and serving.

A safe default is to treat every new upload as untrusted and quarantine it until checks finish. If something slips through, it won’t be served publicly by accident.

For images, avoid serving the original. Resize and re-encode (decode the image, then write it back as a fresh PNG or JPEG). This strips many hidden payloads and removes messy metadata.

For documents, put strict limits on pages, size, and extraction time. PDFs and Office files can be huge, nested, or malformed. Fail closed if processing takes too long. If you need previews, generating a safe image preview is often safer than rendering the document in the browser.

Never render user-provided HTML or SVG directly. If you must accept them, convert to a safe format first (like a raster image) or only allow download with headers that prevent inline execution.

When serving files back, a few rules do most of the work:

- Don’t serve uploads from your main app origin

- Use signed URLs or a download endpoint that checks access

- Force download for risky types and set headers to prevent inline execution

- Track status (quarantined, approved, rejected, deleted) and log key events (user, IP, hash, decision)

Example: a founder uploads a “logo.svg” for a landing page. If you render it inline, it can execute in some browsers. If you convert it to PNG and only serve the PNG, the risk drops fast.

Malware scanning options and practical tradeoffs

Malware scanning isn’t always required for a prototype, but it becomes worth it quickly when uploads are shared with other users, opened by your team, or processed into previews. If your app handles invoices, resumes, ZIPs, Office docs, or anything that gets downloaded, scanning is a practical part of file upload security.

If uploads are only images used for avatars, you can sometimes skip scanning early and reduce risk by re-encoding images and rejecting anything that isn’t a real image. Once you have real users, scanning is often cheap insurance.

Most teams choose one of three approaches: managed scanning in their cloud stack, a third-party scanning API, or self-hosted antivirus in a worker. The “best” choice is usually the one you’ll actually keep running and monitoring.

A safe default is to scan on upload before any processing (thumbnailing, parsing, preview generation), and only allow serving after the file is marked clean. If you add scanning later, scanning existing files “at rest” helps you clean up old data.

When a scan is positive, treat it like a security event, not a UI error: block access immediately, quarantine the object, notify the owner and your team, and keep an audit trail (user, time, hash, result).

Step-by-step: a safe upload flow you can implement

Good upload security is mostly about doing the same boring checks every time, in the same order, before a file becomes reachable by other users.

1) Receive to a temporary area

Accept uploads only into a temporary location (temp bucket or temp folder) that is never public.

- Enforce limits at the door: size, file count, timeouts, and basic rate limits

- Treat the filename as untrusted and generate your own storage name

- Validate the real file type using magic bytes and an allowlist

2) Inspect, store, and serve safely

Before anything is visible in the app, scan and isolate it. If you can’t scan yet, keep it private and restrict access.

- Scan and quarantine; if scanning fails or flags the file, don’t attach it to user content

- Move approved files into private storage with tight permissions and clear metadata (owner, purpose, created_at)

- Serve via short-lived signed URLs or a proxy endpoint that checks authorization

Set automatic cleanup. Expire temp uploads that were never used, and delete old files you no longer need. This prevents mystery storage growth and reduces blast radius.

Common mistakes that cause public bucket accidents

Most “public bucket” incidents aren’t clever hacks. They’re small convenience choices that quietly become permanent and then get copied into production.

A classic mistake is setting the whole bucket to public just to make previews work during a demo. Another is returning direct public URLs from your API because it’s simpler than signed URLs or a download endpoint. If names are predictable (like invoice.pdf), people can enumerate them. Even if names are random, a leaked link becomes a permanent leak when the object is public.

A few red flags show up again and again:

- A browser-based cloud SDK that can write to storage

- One key with broad “read/write everything” permissions

- Signed URLs or tokens ending up in logs or analytics

- “Temporary” ACL settings copied into production

Safer patterns are usually just as fast:

- Keep storage private by default and serve via signed URLs or your app

- Upload to a private “incoming” area, then promote approved files

- Keep credentials server-side; give clients narrow, short-lived upload tokens

Quick checklist before you ship

If you only do one pass before launch, focus on the controls that stop the most expensive mistakes.

Limits and validation

- Enforce a hard max size on the server and add basic rate limits per user or IP

- Verify file type using magic bytes, and treat MIME mismatches as suspicious

- Re-encode risky formats when possible instead of serving originals

Storage and access

- Store uploads in private storage by default, with least-privilege roles

- Never ship storage keys or signing secrets in frontend code

- If you accept PDFs, Office files, ZIPs, or outside content, plan for scanning and quarantine

Reversibility

- Have a kill switch: rotate credentials, revoke tokens, block public access at the bucket policy level

- Make deletion fast: remove a file and its derivatives, and keep logs to find impacted users

Next steps if your AI-built app already has upload risks

AI-generated prototypes often get uploads working, but miss the guardrails that matter in production. Typical symptoms are permanent public URLs, uploads that work without being logged in, no max file size, and servers that trust the browser-provided MIME type without checking the file’s contents.

If you need someone else to verify the risk quickly, it helps to gather: the repo (or a minimal copy with upload code and config), your storage settings (public/private and access rules), where uploads go (browser-to-bucket vs through your server), a few upload logs, the file types you allow, and the limits you want.

If you inherited an AI-built codebase from tools like Lovable, Bolt, v0, Cursor, or Replit, FixMyMess (fixmymess.ai) focuses on repairing exactly these production blockers: missing auth checks, weak validation, unsafe filename handling, overly broad cloud storage permissions, and missing quarantine or scanning gates. A free code audit is often enough to get a concrete punch list of what to fix first, without guessing.

FAQ

What’s the first thing I should do to make uploads safer in a prototype?

Start with strict size limits, timeouts, and basic rate limits on the server, even for a demo. Those three controls prevent surprise bills, slow uploads, and simple bot abuse before you add anything fancy.

Is checking the file extension or MIME type enough?

No. Extensions and browser-sent MIME types are easy to fake. Validate the file by checking its actual contents (magic bytes) and only allow the exact types you support.

Which file types are safest to accept early on?

Use an allowlist and reject everything else by default. For many prototypes, sticking to JPEG/PNG for images and PDF for documents is a practical baseline, then expand only when you have a clear need.

Why are filenames a security risk, and what’s the safer pattern?

If you store using the user-provided name, you can get path traversal, overwrites, and confusing Unicode tricks. Generate your own storage name (like a random ID), keep the original name only for display after cleaning it, and never build filesystem paths from it.

Should my upload bucket be public so users can view files easily?

Keep uploads private by default and avoid storing them in any public web folder or public bucket. Serve files through an endpoint that checks access or via short-lived signed URLs so a leaked URL doesn’t become a permanent leak.

What’s risky about ZIP or Office files compared to images?

ZIP and Office formats are containers, so they can hide scripts, macros, or unexpected structures. If you must accept them, use tighter size limits, quarantine first, scan for malware, and avoid rendering them inline in the browser.

How do I safely show previews for uploaded files?

Treat new uploads as untrusted until checks finish, then create safe outputs for viewing. Re-encode images (decode and write a fresh JPEG/PNG) and prefer generating previews (like images) instead of rendering documents directly in the browser.

What limits should I set to avoid abuse and big cloud bills?

Start with a hard max size per file, a max total request size, and upload timeouts, then add per-user daily caps and burst rate limits. Clear error messages help real users fix issues fast, while rate limits and timeouts reduce slow-drip and retry abuse.

Do I need malware scanning for a prototype?

If uploads are shared, downloaded, or opened by your team, scanning is worth it early. If you only accept avatars and you re-encode them, you can sometimes delay scanning, but plan to add it as soon as real users and real documents show up.

How can I tell if my AI-built app has dangerous upload settings?

Common signs are permanent public URLs, uploads that work without login, no server-side max size, trusting the browser’s MIME type, and broad cloud storage permissions. If your AI-built app has any of these, FixMyMess can run a free code audit and quickly give you a concrete punch list to fix uploads and ship safely.