Payments in AI-generated apps: a checklist for real traffic

Payments in AI-generated apps can fail in quiet ways. Use this checklist to prevent webhook, state, refund, and paid-but-not-activated bugs.

Why payment bugs show up only after launch

Payment flows often look fine in testing because tests are neat. You click “Pay”, you get a success screen, and everything happens in the expected order.

Real traffic is messy. Users refresh, close tabs, switch devices, and retry when a spinner hangs. Payment providers also retry webhook deliveries, send events out of order, or delay them for minutes. If your code assumes “one click equals one clean success”, it will eventually break.

A common symptom is the “paid but not activated” bug. The customer is charged and even sees a receipt, but your app never unlocks the feature, credits, or subscription. From the user’s point of view, it looks like you took their money and gave nothing.

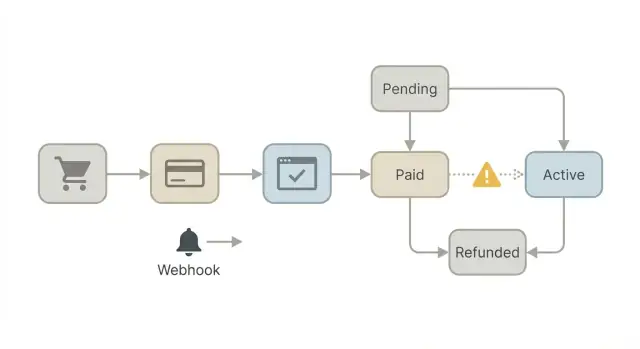

This usually happens because there are more moving parts than the UI suggests. A typical setup includes:

- The client (browser or mobile app) showing payment status

- Your server creating a checkout/session and deciding what to unlock

- The payment provider confirming the charge

- Webhooks telling your server what really happened

- Your database storing the source of truth (what the user has access to)

Many AI-generated prototypes wire these parts together in a “happy path” that only works when timing is perfect. Under load, small issues show up: duplicate requests, two webhooks for the same payment, a database write that fails once, or a race where the UI says “success” before the server finishes activation.

The goal is simple: predictable outcomes even with retries and delays. If the provider sends the same event five times, activation should happen once. If the webhook arrives late, activation should still happen. And if something fails halfway, your system should land in a known state that you can safely retry.

If you inherited a prototype with these problems, FixMyMess often starts by auditing the full flow end-to-end, then making the server and database the source of truth instead of the UI.

Map your payment flow before you change code

Payment bugs are often “logic bugs”, not “Stripe bugs”. Before you touch code, draw the flow on paper (or a doc) and label what your app believes at each step. This is especially true for payments in AI-generated apps, where the happy path is coded, but edge cases are missing.

Start by listing the payment events your business actually relies on. Not every provider uses the same names, but you usually care about a small set: a successful payment, an invoice marked paid, a refund, and a dispute or chargeback. If you cannot point to where each event is handled, you do not have a complete payment system yet.

Next, decide your source of truth. A browser redirect that says “success” is not proof of payment. The most reliable signal is the provider telling your server what happened (usually via webhooks), with the provider API as a backup for verification. Write this down as a rule: “The server activates access only after it can confirm payment from the provider.”

Be explicit about what you will never trust from the browser:

- Any “paid=true” flag

- Price, plan ID, or user ID sent from client code

- The right to mark an order as complete

Finally, write down the few states your app needs, and keep them boring. For example: Created, PaymentPending, Paid, Active, Refunding, Refunded, Disputed, Canceled. The goal is that every event moves an order from one state to another, and nothing else.

A quick reality check: if a user pays in one tab, closes it, and opens your app later, can your server still activate them correctly? If the answer depends on the redirect page, you will see “paid but not activated” tickets at real traffic. Teams like FixMyMess often start fixes by rebuilding this map first, because it makes the missing checks obvious.

Webhooks: idempotency and duplicates

Payment webhooks are not “send once.” Providers retry when your server is slow, when you return a non-2xx response, or when their network glitches. So the same event can arrive multiple times, and events can arrive out of order. If your code assumes a single clean delivery, you will eventually see double-activation, double-emails, or double-credits at real traffic.

The simplest rule: pick one unique identifier for the transaction and treat it as the source of truth. Depending on your provider, that might be a payment intent ID, checkout session ID, invoice ID, or subscription ID. Store it on your user or order record as soon as you create it, before you redirect the customer.

Idempotency means every “write” operation can run twice without changing the result. The webhook handler should first record that it saw a specific event ID (or a provider-specific unique event identifier), then do the business change only if that event has not been processed yet. Make this check atomic (one database transaction), so two webhook deliveries racing each other cannot both win.

A small pattern that works well for payments in AI-generated apps:

- Store provider event ID in a

processed_eventstable with a unique constraint. - Store a single transaction ID on the order (intent/session/invoice).

- Make activation a single update like “status: pending -> active” that can be retried.

- If you get an event for an unknown transaction ID, log it loudly and keep the payload.

- If you get an “already processed” event, return 200 and move on.

A realistic failure: an AI-built webhook creates access on payment_succeeded, and also creates access on invoice_paid. If both fire, the user gets two entitlements. Fixing this is often a “one table, one unique key, one transition” job - the kind FixMyMess audits quickly when payments start acting weird under load.

Webhooks: security and secret handling

Webhooks are how your payment provider tells your app what really happened. If you treat them like “just another POST request”, you can end up activating accounts for fake events, missing real failures, or leaking keys. This is a common weak spot in payments in AI-generated apps because the code often works in light testing, then breaks under real traffic and real attackers.

The first rule is signature verification, and you should fail closed. That means: if you cannot verify the signature, you do nothing (no activation, no status change), and you return an error so you can see it in logs. Don’t accept events based on “it has the right fields” or a shared secret passed in the JSON body.

A simple security checklist that catches most issues:

- Verify the webhook signature using the provider’s official library, with the exact raw request body.

- Reject requests with missing signature headers, wrong timestamps, or invalid payload formatting.

- Keep secrets on the server only (never in frontend code, never committed to the repo).

- Rotate keys if they were ever exposed, even briefly.

- Use separate endpoints and secrets for test vs live.

Test and live mixups cause painful bugs: you see a “paid” event in test, but try to activate a live user, or you store the wrong customer IDs. Make the environment explicit in config, and store the provider account and mode alongside each transaction.

For debugging, log context, not card data. Record things like event ID, event type, provider account, order/user ID, and the internal state before and after handling. Avoid storing full payloads if they include personal data. If you inherited an AI-generated codebase with hardcoded keys or skipped signature checks, FixMyMess can audit and patch this quickly as part of a remediation pass.

State machines: make activation deterministic

A lot of payments in AI-generated apps fail in the same place: the app treats “payment happened” and “user got access” as two separate, loosely connected events. That works in tests, then breaks when real users refresh, open multiple tabs, or a webhook arrives late.

A simple payment state machine makes this predictable. It forces you to name each stage, record it, and only allow specific moves between stages. The goal is boring behavior: the same inputs always produce the same outcome.

Start with explicit states and allowed moves

Pick a small set of states you can explain to a teammate in 30 seconds. For example, an order or subscription can move through: created, awaiting_payment, paid, active, canceled, refunded. Then decide which transitions are valid and reject the rest.

A quick rule set that prevents most weird bugs:

- Only one path grants access: paid -> active.

- “active” can only happen if a payment record exists and is verified.

- Refunds and cancellations must move to a terminal state that removes access.

- Duplicate events (two webhooks, two redirects) must not change the result.

- Unknown states should fail closed (no access) and alert you.

Make activation atomic, even when events arrive out of order

Your riskiest moment is activation. Record the payment and grant access in one atomic operation (a single database transaction, or a job that uses a lock and re-checks state before writing). If you can end up with “paid” but not “active”, your support inbox will find it.

Plan for delays and racing events. A user might return from the payment page before the webhook arrives. In that case, show “Payment processing” and poll for status, rather than guessing. If the webhook arrives late, it should still be able to activate the user safely, without creating a second subscription.

When FixMyMess audits broken payment flows, the most common fix is adding this state machine and enforcing transitions everywhere activation is touched, not just in one controller.

Preventing “paid but not activated” issues

The “paid but not activated” bug usually happens when the payment succeeds, but your app never runs the one piece of code that flips the user into a paid state. It is common in payments in AI-generated apps because the code often mixes browser redirects, webhooks, and database writes without a clear source of truth.

The safest fix is to create a single server-side “grant access” function and treat it like a door with one lock. No matter how many times you call it, the result should be the same: the user ends up with the right plan, the right seat count, and an activation timestamp, and you do not double-create subscriptions or entitlements.

Avoid granting access from the browser redirect alone. Redirects can be blocked, users can close the tab, mobile browsers can drop state, and attackers can fake a “success” URL. Use the redirect only to show a “processing” message, then confirm payment on the server by checking the payment provider status (or a verified webhook event) before calling your grant function.

Make activation rules explicit

Keep the rules short and readable so you can test them. A good pattern is to compute an “entitlement” object and store it:

- Plan (name and limits)

- Seats (count and who is assigned)

- Trial status (active/expired)

- Coupon effects (what changes and for how long)

- Effective dates (start, renewal, cancellation)

Add a reconciliation safety net

Even with perfect webhooks, things fail at real traffic levels. Add a small scheduled job that finds users who look paid but are inactive, then repairs safely by re-running the same grant function.

Example: a customer pays, the webhook times out, and your DB write never happens. The next hour, your reconciliation job checks “payment succeeded in provider” but “no active entitlement in DB”, then grants access and logs what it changed.

This is the kind of issue FixMyMess often finds in AI-generated prototypes: access logic scattered across routes, webhook handlers, and frontend code. Consolidating it into one idempotent grant path usually removes the bug class entirely.

Refunds, disputes, and reversals

Refunds are where many payments in AI-generated apps quietly break. The “happy path” usually works, but real customers ask for partial refunds, change plans mid-cycle, or get refunded in several steps. If your code assumes “one payment, one refund,” you will eventually grant the wrong access.

Treat refunds as their own events, not as a simple on/off switch. Track the total refunded amount over time, and compare it to what was paid for the specific invoice or charge. This avoids bugs where a second partial refund accidentally looks like a full refund, or where a later refund overwrites earlier history.

Decide ahead of time what a refund means for access. The best answer depends on your product and your risk tolerance, but it must be consistent and easy to explain:

- Remove access immediately (good for high-risk digital goods)

- Keep access until the end of the paid period (good for subscriptions with clear terms)

- Freeze access and send to manual review (good when fraud is common)

Disputes and chargebacks need stricter rules than refunds. When a dispute opens, assume the payment may be reversed even if the user still shows as “paid” in your database. A safe default is to freeze access, notify the owner, and keep an audit trail: who changed access, when, and which payment event triggered it.

Most importantly, don’t let refund-related events push your payment state backward in a way that reactivates someone by accident. For example, a late “payment_succeeded” webhook retry should not flip a user back to active after a refund or dispute. Make your state transitions one-way for risk events (refund, dispute, chargeback), and require an explicit human action to restore access if needed.

If your app is already showing confusing “active after refund” behavior, FixMyMess can audit the code paths and webhook handling and tell you exactly where the state is being overwritten.

Observability: logs and signals you will actually use

When payments break, the first question is simple: what happened, in what order, and what did the system decide? In payments in AI-generated apps, the code often “works” in happy-path testing but fails under retries, duplicates, and timing gaps. Good observability turns guessing into a quick answer.

Build a minimal payment timeline

Aim for one clear, searchable story per purchase. You do not need fancy dashboards to start. You need consistent identifiers and the final outcome.

Capture these fields on every payment-related action:

- user_id, order_id (or checkout/session id), provider_payment_id

- webhook_event_id, event_type, received_at, processed_at

- current_state and new_state (your internal payment state)

- activation_result (activated/denied) and reason (if denied)

- idempotency_key and whether it was a duplicate

With that, you can answer “Did we receive the webhook?”, “Did we process it twice?”, and “Why didn’t access turn on?” in minutes.

Track a few signals that catch real bugs

Pick metrics that map to customer pain and money risk, not vanity numbers.

Watch these metrics daily:

- webhook verification failures and signature mismatches

- webhook processing failures and retry counts

- activation latency (paid to activated) percentiles

- count of “paid but inactive” users (mismatch)

Add simple alarms for trends, not single blips: a rising webhook verification failure rate, a spike in paid-but-inactive mismatches, or activation latency suddenly jumping.

A quick example: a user pays, sees a success screen, but stays locked out. Your timeline shows the payment succeeded, the webhook arrived twice, the first attempt failed on a database timeout, and the retry was skipped because the idempotency check used the wrong key. That points directly to the fix.

If your logs are scattered across files or missing event IDs, teams like FixMyMess often start by normalizing this timeline during a code audit so payment bugs are reproducible before changing logic.

Common mistakes that AI-generated code often makes

A lot of payment failures in payments in AI-generated apps come from one pattern: the code “looks right” in a demo, but it treats a payment as a single moment instead of a sequence of events.

One common trap is trusting the client. A “payment successful” page is not proof. People close the tab, browsers block redirects, and mobile networks drop calls. If your app grants access because the frontend says “success,” you will eventually see users get access without a completed payment, or paid users get stuck.

Another frequent issue is splitting setup into separate steps that are not atomic. For example: create user, then create subscription, then add a row that grants access. If step 2 fails after step 1, you now have a half-created account. Later, a webhook arrives and tries to activate something that does not exist in the expected shape.

Here are mistakes that show up a lot in AI-generated payment code:

- Treating a redirect return as the final truth instead of verifying the payment on the server

- Writing webhook handlers that are not idempotent, so retries create duplicate subscriptions or double-activate access

- Assuming webhooks arrive in order, then breaking when “cancel” arrives before “paid”

- Mixing test and live modes during a release, so live webhooks hit test keys (or the wrong endpoint)

- Storing secrets in client code or logs, then getting keys rotated mid-incident

A realistic example: a user pays, gets redirected back, but the activation call times out. They refresh and try again, creating a second “pending” record. Meanwhile the payment provider retries the webhook, and your handler creates a second subscription because it keys off “email” instead of a stable payment ID. Now support sees “paid but not activated,” plus an extra subscription.

If you inherited code like this, FixMyMess can audit the flow quickly and point out where state, webhooks, and access rules can drift apart before it hits real traffic.

Quick checklist before you ship

For payments in AI-generated apps, the last week before launch is when small “good enough” shortcuts become expensive bugs. Use this short checklist to catch the problems that only show up under retries, delays, and real customer behavior.

Before you ship, confirm these are true:

- Your webhook handler validates the provider signature and only returns a success response after you have saved the event and applied its effects.

- Every database write related to a charge, subscription, or invoice is idempotent, keyed by the provider’s unique transaction or event ID (so retries do not double-create records).

- You can point to a simple payment state machine (even a diagram on paper), and your code blocks impossible jumps like going from "refunded" back to "active".

- You have a reconciliation check for “paid but inactive” cases (for example: scan for successful payments without an activated account, then auto-fix or alert).

- You have triggered at least one refund and one dispute/chargeback style event in a staging-like environment and confirmed the user’s access and internal records update correctly.

A quick reality check: imagine a customer pays, closes the tab, and your activation happens in a background job. If the job fails once, or the webhook arrives twice, do you end up with “paid but not activated” or “activated without payment”? Your checklist above should make both outcomes impossible.

If you inherited an AI-generated checkout and you are not sure where to start, FixMyMess can run a free code audit focused on webhook safety, idempotency, and activation logic, then help you patch the risky parts quickly before real traffic hits.

A realistic example and next steps

A founder launches a small membership app built with an AI tool. Payments look fine in testing, but once real users arrive, a pattern appears: people pay, then land back in the app still marked as “trial”. Support tickets pile up, and some users try paying twice.

The usual root causes are boring, but painful:

- Activation happens only on the success redirect. If the user closes the tab, loses connection, or the redirect fails, the app never flips them to “paid”.

- Webhooks are processed twice (or out of order) and the code is not idempotent, so the second delivery overwrites the correct state or creates a duplicate subscription record.

- The app listens for the wrong event or reads the wrong field (for example, treating “payment_intent.succeeded” like “checkout.session.completed”), so some payments never match a user.

A safe fix is to make the server the source of truth, and make the logic predictable.

A safer fix path

Start by adding a simple payment state machine per user (trial -> pending -> active -> past_due -> canceled). Then:

- Confirm payment server-side using the processor’s API or a verified webhook, not the redirect.

- Make webhook handlers idempotent (store event IDs, lock per user or per subscription).

- Add a small reconciliation job that backfills: “paid but not active” users are rechecked and corrected.

Once that’s in place, the redirect becomes just a nice UX step, not the only activation trigger.

Next steps

If you’re dealing with payments in AI-generated apps and the same bugs keep coming back, it may be faster to do a focused audit before patching more code. FixMyMess (fixmymess.ai) can review the codebase, find the activation and webhook failure points, and repair the flow with human-verified fixes so it holds up at real traffic levels.