Refactor messy codebase structure without breaking production

Refactor messy codebase with a practical plan for folder boundaries, naming, module extraction, and small PRs that keep behavior stable.

What a messy codebase structure really means

A messy codebase structure isn't "a lot of files." It's when the layout stops matching how the product works. You can't tell where a change belongs, so every change feels risky.

In real repos, it usually shows up as mixed concerns: UI code talking directly to the database, auth checks scattered across pages, and "utils" folders that quietly hold half the business logic. Another common smell is circular imports (A imports B, B imports A). They can create strange runtime behavior and push people toward hacks just to make the app start.

Naming is the quieter problem. You'll see three ways to name the same thing (userService, users.service, user_manager), or folders that mean nothing (misc, temp, old2). People duplicate code because they can't find the right place, and the mess compounds.

You feel structure problems in day-to-day work more than in architecture diagrams:

- Small changes take hours because you chase dependencies across the repo.

- Bugs repeat because fixes land in one place while the real behavior lives in another.

- Releases feel scary because one "tiny" edit can break something unrelated.

A cleanup is worth it when structure is the main thing slowing you down or causing avoidable bugs. If the product is stable, changes are rare, and the team understands the current layout, a big refactor can wait. Often the best move is "touch it, tidy it": improve structure only in the area you're already changing for a feature or bug.

"Not breaking everything" means behavior stays the same while the structure changes. Users shouldn't notice. The payoff is safer changes: smaller diffs, clearer boundaries, and fewer surprises during testing and release.

Set goals and guardrails before you touch code

Refactors go faster when you can answer one question: what are we trying to improve? Pick one primary target, like faster changes, fewer bugs, or easier onboarding. If you try to fix everything at once, you'll spend a week moving files around without making the system easier to work on.

Next, write down what must stay stable. Stability isn't just "tests pass." It's the real contract your app has with users and other systems.

Agree on guardrails before the first commit:

- Non-negotiables: public APIs, database schema, routes, and key UI flows that must not change.

- Scope: what's in-bounds, and what's off-limits (for now).

- Time box: a clear limit (for example, 2-3 days) before you reassess.

- Proof: which checks must be green (tests, lint, build, plus a short smoke test).

- Done means: "these folders are cleaned and documented," not "the whole repo is perfect."

Example: you inherit an AI-generated app where auth works "most of the time," routes are duplicated, and files live in random places. Your guardrails might be: don't change the login flow, session cookies, or database tables this week. The goal is only to put auth behind one module and move related files into a single folder with consistent names. That gives you a win you can ship without creating a new mystery bug.

If you're working with others, put guardrails in writing and get a quick yes. It prevents mid-refactor debates and keeps reviews focused on outcomes, not opinions.

Quick map of the current structure (30 to 60 minutes)

Before you move folders around, spend one focused hour making a rough map. This reduces risk because you stop guessing where behavior starts and where it spreads.

Start with entry points: where the system wakes up and begins doing work. Many apps have more than one: a web server, a scheduled worker, a queue consumer, a CLI script, and sometimes a migration runner.

Then find the pain: the files and folders people touch constantly. High churn often means those files do too much, or everything depends on them.

Keep a simple map open while you work:

- 3 to 6 entry points (what runs first, and how it starts)

- 5 to 10 high-churn files or folders (where changes keep landing)

- 3 to 5 dependency hot spots (imported by lots of other modules)

- One sentence for each top-level folder's purpose (even if it's ugly)

A dependency hot spot is where refactors go to die. A quick tell is a single "utils" file that contains auth helpers, date formatting, database code, and API calls. If it's imported everywhere, every change is risky.

Keep the map honest, not flattering. "src/helpers: random stuff we didn't know where to put" is useful. Later, you can turn that sentence into a plan.

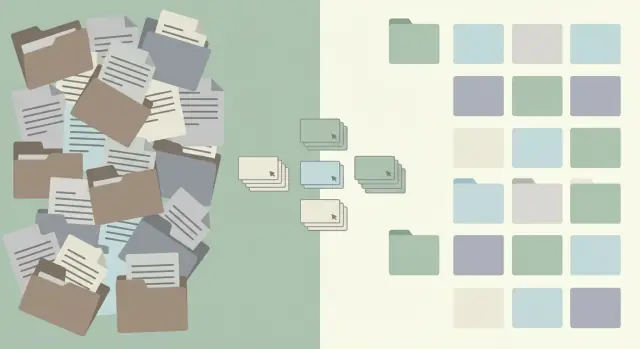

Define folder boundaries that reduce coupling

If you want to reorganize without breaking production, start by drawing clear borders. The goal is simple: a change in one area shouldn't force edits all over the repo.

Pick a folder model you can explain in one sentence

Choose the simplest model that matches how your team thinks:

- By feature: everything for "billing" lives together (UI, logic, data).

- By layer:

ui/,domain/,data/are separate and features sit inside them. - Hybrid: feature folders at the top, with

ui/,domain/,data/inside each feature.

Any of these can work. What matters is that "Where does this file go?" has an obvious answer.

Write plain rules for what belongs where

Define boundaries with everyday language. For example:

- UI: components, screens, forms, and display logic.

- Domain: business rules and decisions (price calculation, eligibility checks).

- Data access: API clients, database queries, and persistence.

Then add a short "do not cross" list to prevent accidental coupling as you refactor:

- UI doesn't import from data access directly.

- Domain doesn't import UI.

- No direct DB calls outside data access.

- No reading env secrets outside a single config module.

- No feature folder reaches into another feature's internals.

A quick scenario: if a checkout screen needs an order total, it should call a domain function (like calculateTotal). That function can call data access through a small interface, not through raw SQL or a direct API client.

Finally, decide ownership. Name a reviewer (or small group) for each area so boundary breaks get caught early.

Naming conventions and small rules that keep order

Refactors often fail for a boring reason: people don't know where to put the next file, so the mess starts growing again. Naming conventions sound picky, but they remove daily decisions and stop "just this once" exceptions.

Pick conventions your team will actually follow. If a rule needs a debate every time, it's too strict or too clever. The goal is consistency, not perfection.

A few basics to write down:

- File and folder names: pick kebab-case (

user-profile.ts) or camelCase (userProfile.ts) and stick to it. - Singular vs plural: for example, use singular for module folders (

invoice/) and plural only for collections (invoices/). - Exports: prefer named exports for shared code; avoid default exports unless there's a clear reason.

- Index files: either ban them or limit them to re-exporting the public API, so imports stay predictable.

- One concept per file: if a file grows past a screen or two, split it by responsibility.

A small "golden example" folder helps more than a long document. Keep it tiny and close to what you build most often:

features/

auth/

api.ts

routes.ts

components/

LoginForm.tsx

index.ts

When someone adds a new auth screen, they can copy the pattern without guessing.

One lightweight rule for new code helps the refactor stick even if the cleanup isn't finished:

- New files follow the new naming rules and live in the new folders.

- "Touch it, tidy it": if you modify a file, move it to the right place or fix the name.

- No new junk drawers like

misc.

If this feels hard to enforce, it's usually a sign the structure still doesn't match how the app works.

Step by step: extract one module safely

Pick a small, low-risk target first. A good starter is a shared utility that many files import (date formatting, feature flags, input validation) or a single feature that's mostly self-contained. If you try to pull out a core domain area on day one, you'll spend your time chasing surprises.

A safe refactor changes the shape of the code without changing what it does. The trick is to create a boundary, then move code behind it bit by bit.

A safe extraction sequence

Start by writing the promise of the new module in one sentence: what it does, and what it won't do. Then:

- Freeze behavior behind an interface. One exported function or class is enough. Keep the internals ugly for now; make the outside simple.

- Move in small commits. Update imports as you go. If you must rename things, do it after the move so diffs stay readable.

- Check after each move. Run the app and tests. If you don't have tests, do a quick manual check of the one flow that uses it.

- Delete old code last. Only after you can prove nothing depends on it (search imports, check runtime logs, confirm no duplicate copies remain).

- Add a few focused tests at the boundary. One happy path, one edge case, one failure case is usually enough.

Example: you notice three different files answer "is the user logged in?" in slightly different ways. Create an authSession module with getSession() and requireUser(). First, make those functions call the old code. Then move the logic inside the module, update one caller at a time, and add 2 to 3 tests that lock down the expected outcomes.

Extraction also surfaces hidden coupling: globals, mixed concerns, secret values in random files, and "temporary" helpers that became permanent.

How to ship the refactor using incremental PRs

This work is safest when you treat it as a series of small deliveries, not one big rewrite. Incremental PRs keep the blast radius small. When something breaks, you can spot it quickly and roll back without panic.

Keep PRs small and boring

Aim for one kind of change per PR: move one folder, rename a group of files, or extract one module. If you feel the urge to "fix a few things while you're here," write it down and do it later.

Do mechanical changes first: moves, renames, formatting, import path updates. They're easy to review because behavior stays the same.

Once structure is stable, do behavior changes in separate PRs (logic fixes, data shape changes, error handling). Mixing structure and behavior is how refactors turn into mystery bugs.

Write PR descriptions that help reviewers verify

Make review easier by including:

- What changed (one sentence)

- The risk (what could break, and where)

- How to verify (a short manual test plus key automated checks)

- Rollback plan (usually "revert this PR")

Example: "Moved auth-related code into modules/auth and updated imports. Risk: login route wiring. Verify: sign up, log in, log out, refresh session.".

If more than one person is working, agree on an order that avoids conflicts. Merge boundary PRs first, then extractions that build on the new layout. Assign ownership so two people don't edit the same high-churn files at the same time.

Keep behavior stable while the structure changes

The goal is boring: the app should behave the same for users. Most refactors fail because small behavior changes slip in unnoticed.

Start with smoke checks that match how the product is used. Keep the list short so you'll actually run it every time:

- Sign up, login, logout (and password reset)

- Create the main object in your app (order, post, project, ticket)

- Update and delete that object

- One money action (checkout, invoice, subscription change), if you have it

- One message action (email, notification, webhook), if you have it

Tests are tripwires, not a perfection project. If coverage is weak, write 2 to 5 high-value tests around the flows above, then stop. A couple of end-to-end or integration tests usually catch more refactor mistakes than dozens of tiny unit tests.

Watch for silent failures. Auth can break without obvious errors (cookies, session storage, redirect paths). Payments and emails can fail "successfully" if callbacks aren't wired or background jobs aren't running. Queues can drop tasks if job names or import paths change during extraction.

Make failures visible fast. Confirm you can see logs and errors in one place, and that errors include enough context (user ID, request ID, job name). During the refactor, add a few targeted log lines around critical boundaries (auth, billing, outbound emails), then remove them once things settle.

Common traps that make refactors go sideways

Most refactors fail when small changes pile up until nobody is sure what's safe anymore. Watch for these traps early.

The "it still builds" trap

Moving files can feel harmless, especially when tests are green. But if you move things without deciding what the public interface is, you end up breaking imports across the app, or forcing everyone to "just update the path" in dozens of places.

A safer pattern is to keep stable entry points (for example, an index file per module that defines the public API) and change internal paths behind that interface.

Also avoid creating a new junk drawer as a quick fix. A fresh misc or utils folder turns into the same problem in a week. If something doesn't have a clear home, treat that as a signal your boundaries are unclear.

Hidden backdoors between modules

Extraction isn't done when files are moved. It's done when the module can stand on its own.

The usual backdoors are cross-imports (module A quietly imports module B) and shared globals (config objects, singletons, mutable caches) that let code reach across boundaries.

Traps that commonly derail review quality:

- Renaming lots of files and symbols at the same time as moving folders

- Mixing refactor work with new features

- Leaving both the old and new API in place "temporarily" and never removing the old path

- Making a giant PR that reviewers can only skim

- Accidentally changing behavior (for example, moving auth code and altering middleware order)

Example: a team extracts an auth module, but a few screens still import a shared currentUser global from the old folder. Everything looks fine until production, where a cold start loads modules in a different order.

Quick checklist for each refactor PR

Small PRs are how you reorganize structure without turning production into a guessing game.

Before you open the PR

If you can't explain the change in two sentences, the PR is probably too big.

- Keep scope to one boundary fix, one rename set, or one module move.

- List the entry points you might affect (routes, CLI commands, background jobs, imports from other packages).

- Note a rollback plan (usually "revert this PR"; sometimes a compatibility export for one release).

- Run lint and tests locally, and write down 2 to 3 smoke checks.

- Confirm there's no behavior change unless the PR title says so.

Concrete example: if you're moving auth helpers into a new module, call out the login route, token refresh, and middleware imports as your entry points. Smoke checks: sign in, sign out, refresh token, load a protected page.

After you open and merge the PR

Do a quick sanity pass before the next slice:

- Check you didn't introduce circular imports (a build plus a dependency check usually reveals it).

- Remove any temporary folders created during the move, or rename them into the final home.

- Make sure the team agrees where new files go now (a short comment in the PR is often enough).

- Update simple notes: a short README in the folder, or a brief comment explaining the folder purpose.

- Confirm the PR didn't quietly change public APIs (exports, file paths others import).

Next steps: keep momentum (and know when to get help)

Pick one small, real feature and use it as your proof path. If you're working from an AI-generated prototype, a common starting slice is: auth checks pulled out of UI components, data access gathered into one module, and the UI reduced to rendering.

Refactor one vertical slice first, and postpone the rest. For example: take "Sign in -> load account -> show dashboard" and make it boring and predictable. Move auth checks into one place, pull data access into a single module, and keep the UI focused on display. Save bigger debates (full folder renames, framework switches, perfect domain modeling) for later, once you have momentum and a safety net.

When you explain the plan to non-technical stakeholders, lead with what stays stable: screens, pricing logic, customer data. Then explain what changes internally: fewer production surprises, clearer ownership, and safer handling of secrets.

It's often faster to get help when the code has deep spaghetti (everything imports everything), you see security red flags (exposed keys, unsafe queries), or authentication is already unreliable.

If your codebase came from tools like Lovable, Bolt, v0, Cursor, or Replit and you're spending more time untangling than building, FixMyMess (fixmymess.ai) can run a free code audit to identify the riskiest areas and the safest order to fix them before you start moving everything around.

FAQ

How do I know if my codebase structure is actually “messy” or just big?

A messy structure shows up when you can’t tell where a change belongs, so every edit feels risky. Common signs are mixed concerns (UI touching the database), business logic hiding in “utils,” inconsistent naming for the same concept, and circular imports that create weird runtime behavior.

When is a structural refactor worth doing, and when should I wait?

Do it when structure is clearly slowing delivery or causing repeat bugs, not just because it looks ugly. If the product is stable, changes are rare, and the team can work safely, a large cleanup can wait while you apply “touch it, tidy it” in the areas you already modify.

What guardrails should I set before I start moving files around?

Pick one primary goal, like “changes to auth should be predictable,” and write down non-negotiables such as routes, database schema, and critical user flows. Add a short time box and a clear definition of “done” so you ship improvements instead of moving files forever.

What’s the fastest way to understand a repo before refactoring it?

Spend 30–60 minutes mapping entry points and hotspots before you touch structure. Find where the app starts, what files change most often, and what modules everything imports, then write one honest sentence about what each top-level folder is for.

How do I choose folder boundaries that don’t turn into arguments?

Start with a simple boundary rule you can enforce consistently, like “UI doesn’t call the database” and “secrets only come from one config module.” Then pick a folder model (by feature, by layer, or hybrid) based on what your team naturally talks about, not what looks trendy.

What naming conventions actually prevent the mess from returning?

Keep it boring and consistent so people don’t have to think every time they create a file. Choose one naming style, decide how index files are used, and keep a small “golden example” folder that shows the pattern you want repeated.

What’s a safe way to extract a module without breaking production?

Extract one small module behind a clean interface first, and move callers over one at a time. Keep behavior the same, verify after each move, and only delete old code once you can prove nothing depends on it.

How small should refactor PRs be, and what should I avoid mixing in?

Limit each PR to one type of change and keep refactors separate from behavior changes. If a PR mixes file moves with logic edits, reviewers can’t tell what’s risky, and you’re more likely to ship a “mystery bug.”

What if I don’t have good tests—how do I keep behavior stable?

Start with a short smoke test that matches real user flows and run it every time you move structure. If tests are weak, add a few high-value checks at module boundaries (auth, billing, email) so refactor mistakes show up quickly.

When should I get help instead of trying to refactor an AI-generated codebase myself?

If everything imports everything, auth is already flaky, secrets are exposed, or you see unsafe query patterns, you’ll likely lose time untangling alone. FixMyMess can run a free code audit on AI-generated codebases and quickly identify the riskiest areas and the safest order to fix them, often getting you to a production-ready structure within 48–72 hours.