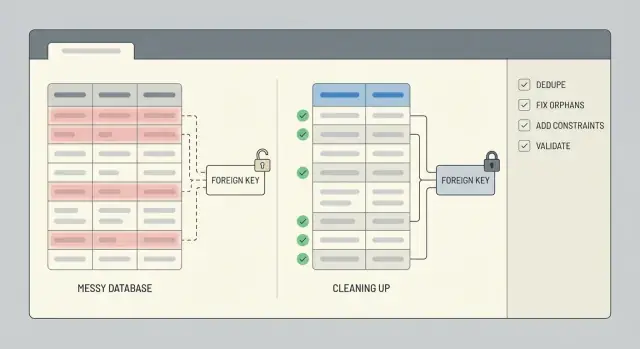

Data cleanup after a rushed prototype: dedupe and integrity repair

Data cleanup after a rushed prototype: deduplication and integrity repair steps to find duplicates, fix orphan rows, enforce constraints, and validate with scripts.

What usually breaks after a rushed prototype

A rushed prototype is built to prove a point, not to protect your data. Rules are often missing, fields change names mid-build, and someone eventually "just edits it in the database" to get past a blocker. If the app was generated by an AI tool, you also see fast copy-paste patterns: overlapping tables, IDs stored as text in one place and numbers in another, and logic that saves the same record twice.

Duplicates show up in boring, expensive ways: two user accounts with the same email but different casing, multiple "active" subscriptions for one customer, or the same order saved once on click and again on page refresh. Sometimes they aren't exact matches. You might see near-duplicates like "Acme, Inc" vs "ACME Inc." or two contacts sharing a phone number.

Broken relationships are just as common. You'll find orders pointing to a user_id that no longer exists, comments tied to a deleted post, or rows that reference 0 or an empty string because the app never validated inputs. These orphaned rows don't always crash the app, but they quietly break totals, dashboards, and exports.

People experience bad data as login issues, wrong totals (double-counted orders, inflated inventory), missing history, and UI screens that work for some records but not others.

Clean up now if you're about to charge money, you need reliable reporting, or support is spending time fixing records by hand. Waiting makes it harder because every new feature writes more data on top of the mess.

Before you touch data: snapshot, scope, and rollback

Cleanup goes wrong when you start editing rows before you know what matters and how to undo changes. Treat this like a controlled operation, not a quick fix.

Start by scoping the parts of the database that affect real people and money. List the tables and the user flows they support: signups, checkout, subscriptions, content publishing. If you skip this, you can dedupe one table and accidentally break a downstream flow that still expects the old shape.

A simple scope note is often enough: users, sessions/auth tables, orders, payments, invoices, subscriptions, and core content tables (posts, comments, files). Also write down the source of truth for each key field (for example, whether you trust a payment provider ID more than an email address).

Next, take a safe snapshot and define rollback before you run a single UPDATE. The snapshot can be a database backup, a point-in-time restore, or an exported copy of the affected tables. Rollback isn't "we'll be careful". It's a written step: how you restore, how long it takes, and who can do it.

Whenever you can, run cleanup on a copy first. A recent production clone in staging is ideal because it contains real edge cases without risking live data. Only move to production once your scripts are repeatable and the results are predictable.

Finally, set a time window. If possible, freeze or gate risky writes (new signups, order creation, background sync jobs) during the cleanup. If you can't freeze, record a cutoff timestamp and limit your changes to records created before that point.

Decide what a duplicate is (and what you will keep)

Before you delete anything, get specific about what "duplicate" means for your app. In a prototype, two rows can look identical to a person but still represent different real users or events. If you guess wrong, cleanup turns into data loss.

Start by picking a source of truth for each entity. For users, that might be the record tied to a verified login, the oldest account, or the one referenced by the most orders. For orders, it might be the row that actually got paid, not the one created during a failed checkout.

Write simple merge rules and stick to them. Decide how you resolve conflicts and how you handle blanks. A few rules cover most cases:

- If one record has a value and the other is null, keep the value.

- If both have values, prefer the verified one or the most recently updated one.

- Don't overwrite audit fields you care about (

created_at,signup_source, and similar fields).

Next, decide the canonical key you'll use to identify duplicates. Common options are email, an external_id from an auth provider, phone number, or a composite like (workspace_id, normalized_email). Be careful: prototypes often store emails with different casing, extra spaces, or plus-addressing variations.

Edge cases are where teams get burned. Shared inboxes (team@), test accounts, imported CSVs with placeholder emails, and AI-generated seed data can all create legitimate repeats. Capture these exceptions up front and keep a short list of patterns you will exclude from dedupe.

Methods to detect duplicates

Start with the simplest signal: two rows that share the same key. Even if your prototype never defined a true key, you usually have something close (email, external_id, order_number, or a natural combination like user_id plus a created-at day).

A quick first pass is a count by the suspected key, filtered to keys that appear more than once:

SELECT email, COUNT(*) AS c

FROM users

GROUP BY email

HAVING COUNT(*) > 1

ORDER BY c DESC;

Next, look for near-duplicates. Normalize the field in the query so you can see collisions you would otherwise miss:

SELECT LOWER(TRIM(email)) AS email_norm, COUNT(*) AS c

FROM users

GROUP BY LOWER(TRIM(email))

HAVING COUNT(*) > 1;

Also check duplicates created by retries. If your app inserts the same event twice after a timeout, you may see multiple rows with the same event_id, provider_charge_id, idempotency_key, or (user_id + exact payload hash). If you don't have those fields, the pattern often looks like identical rows created seconds apart.

Before you delete or merge anything, build a small review sample. Pick the top 20 duplicate groups and inspect them manually so you know what "keep" should mean. Pull full duplicate sets for review, compare timestamps, check whether child rows (orders, sessions, invoices) point to one of the duplicates, and write down the rule you will apply. Save the query that produced your sample so you can rerun it after changes.

Deduplicate without losing important history

If other tables point to a record, deleting it is usually the fastest way to create new problems. A safer approach is to merge duplicates and re-point everything to a single keeper row so history stays connected.

Pick a keeper for each duplicate group, move references from the loser IDs to the keeper ID, then archive losers or mark them inactive. This avoids breaking orders, invoices, messages, and permissions that still need to be tied to the same person or account.

When duplicates disagree, decide up front how conflicts will be resolved. Keep it predictable: prefer verified records over unverified ones, prefer paid/active status over free/inactive status, keep the latest valid values when both look reasonable, and never overwrite non-empty fields with empty fields.

Keep an audit trail so the work is reversible. A tiny mapping table like dedupe_map(old_id, new_id, merged_at, reason) lets you answer "what happened to this user?" months later, and it makes debugging much faster.

Don't forget the data around the row. Profiles, settings, memberships, uploaded files, and notes often live in separate tables. Re-point those child rows first, and watch for uniqueness clashes (for example, two settings rows that must become one).

Run the dedupe in batches (like 100 to 1,000 groups at a time). Smaller batches reduce lock time, make failures easier to isolate, and give you a chance to inspect results between runs.

Find and repair orphaned rows

An orphan is a row that points to something that isn't there. Most often, it's a child row whose parent_id doesn't match any existing parent row. This shows up a lot after a rushed prototype, especially when the app skipped transactions or deleted records without cleaning up related tables.

Start by measuring the problem. A simple left join check tells you how many child rows can't find a parent.

-- Example: orders should reference users

SELECT COUNT(*) AS orphan_orders

FROM orders o

LEFT JOIN users u ON u.id = o.user_id

WHERE u.id IS NULL;

-- Inspect a sample to understand patterns

SELECT o.*

FROM orders o

LEFT JOIN users u ON u.id = o.user_id

WHERE u.id IS NULL

LIMIT 50;

If you use soft deletes, watch out for "hidden orphans": the parent row exists, but it's logically removed (for example users.deleted_at IS NOT NULL). Decide whether those should still count as valid.

Once you know what you're dealing with, pick a repair path based on what the data means:

- Recreate the missing parent when it truly failed to save.

- Reassign the child to a real parent (common after user dedupe).

- Archive or delete the orphaned child if it can't be trusted (test data, partial writes).

- Create an "Unknown" or "System" parent only if your product logic can handle it cleanly.

Whatever you choose, record every change so you can re-run safely. A good pattern is: write changes into a staging table (or mark rows with a batch ID), update in small batches, and log counts before and after.

Enforce integrity with constraints (and the right indexes)

After cleanup, constraints are what keep the same mess from returning next week. Add them only after you've deduped and repaired broken relationships, or you'll block your own cleanup.

Start with primary keys. Make sure every table has one, it's truly unique, and it will never be reused. If your prototype used meaningful IDs (like a user ID based on an email hash), consider switching to a stable surrogate key (like an auto-increment integer or UUID) and treating the meaningful value as a separate unique field.

Then lock down the identifiers your business actually relies on. For many apps, that means a unique constraint on email (often case-insensitive) and on any external_id you get from a payment provider, CRM, or auth system.

Foreign keys prevent orphaned rows. Choose delete behavior that matches reality: sometimes you want to block deletes, sometimes you want to cascade, and sometimes you want to keep history by setting the foreign key to null. Example: if your MVP let you delete a user but left orders behind, you can prevent deletion when orders exist, or keep orders and anonymize the user.

Check constraints catch bad values early. Keep them simple: totals must be >= 0, status must be in an allowed set, required timestamps must not be null, and quantity must be > 0.

Finally, add the right indexes so these rules don't slow everything down. Unique constraints and foreign keys usually need supporting indexes, and it's worth matching indexes to your most common lookups (like orders by user_id).

Step-by-step: build repeatable cleanup scripts

Messy data fixes go wrong when they're done by hand, one-off, or without a clear order. Treat the work like a small release: apply changes in a sequence you can repeat on staging and production.

A simple script structure

Use ordered migrations or scripts that follow the same three phases every time: setup, backfill, enforce. Keep read-only detection queries separate from write steps so you can review what will change before anything is updated.

A practical flow that works in most databases:

- 01-detect.sql (read-only): list duplicates, orphans, and bad values

- 02-setup.sql: add helper tables/columns (for example, a mapping table of old_id -> kept_id)

- 03-backfill.sql: reassign foreign keys, merge rows, archive what you're removing

- 04-enforce.sql: add unique constraints, foreign keys, and needed indexes

- 05-validate.sql (read-only): checks that prove the cleanup worked

Make write scripts idempotent (safe to run twice). Use clear guards like WHERE NOT EXISTS (...), check for column/constraint existence, and prefer upserts into mapping tables. Wrap risky updates in a transaction when possible, and fail fast if expected preconditions aren't met (for example, if a duplicate group has two "active" rows).

What to record every run

Log what changed so you can explain results and spot regressions later. At minimum, record counts per step: rows merged, rows reassigned, rows archived, and rows left unresolved.

A helpful pattern is returning counts from each write step:

-- Example: reassign child rows to the kept parent

UPDATE orders o

SET user_id = m.kept_user_id

FROM user_merge_map m

WHERE o.user_id = m.duplicate_user_id;

-- Example: archive duplicates (guarded)

INSERT INTO users_archived

SELECT u.*

FROM users u

JOIN user_merge_map m ON u.id = m.duplicate_user_id

WHERE NOT EXISTS (

SELECT 1 FROM users_archived a WHERE a.id = u.id

);

Store scripts in version control with a short runbook (inputs, order, expected runtime, rollback notes).

Validate results with quick checks and repeatable tests

The work isn't done until you can prove the database is safer than before. Start by writing down a few before-and-after numbers you can compare every time you rerun the cleanup.

Track metrics that show whether the problem actually shrank: total rows, distinct business keys, duplicate groups, and orphan counts. Save these numbers in a small text file or a table so you can spot regressions later.

Here are a few queries you can rerun after every fix:

-- Row counts (sanity)

SELECT COUNT(*) AS users_total FROM users;

-- Distinct keys (did dedupe work?)

SELECT COUNT(DISTINCT email) AS users_distinct_email FROM users;

-- Duplicate groups (should trend to 0)

SELECT email, COUNT(*)

FROM users

GROUP BY email

HAVING COUNT(*) > 1;

-- Orphans (child rows without a parent)

SELECT COUNT(*) AS orphan_orders

FROM orders o

LEFT JOIN users u ON u.id = o.user_id

WHERE u.id IS NULL;

Numbers help, but they don't replace real-world behavior. Validate a few critical flows in a way that matches how the app is used: can a user sign in, can an order load, does an invoice total still match its order items. Then spot-check 10 to 20 real records end-to-end.

To keep this from breaking again, add lightweight automated checks you can run after every deployment: a script that runs the metrics and fails if duplicates or orphans rise, a constraint check (unique keys, foreign keys) in CI or a release checklist, and a daily job that reports new violations before they grow.

If bad data can still enter (old import jobs, loose API validation), plan ongoing cleanup: block the source, then keep the checks running.

Why duplicates and orphans keep coming back

Duplicates and orphaned rows are rarely a one-time accident. If your app keeps creating them, cleanup only buys time unless you fix the causes in the code and the workflow.

One common trigger is retries. A background job times out, retries, and inserts the same "create order" or "send invite" record again because it has no idempotency key. The job did what it was told. It just did it twice.

Async flows can also race each other. For example, a signup flow creates a user in one request and creates a profile in another. If the profile request runs first or the user insert fails, you get an orphaned profile row. Missing transactions make this worse because half-finished work can get committed.

Human actions matter too. Quick admin edits or "just fix it in the database" moments can bypass the checks your app normally runs, especially when there are no constraints to stop bad writes. Imports add another path: the CSV has emails with different casing, phone numbers with extra characters, or external IDs that aren't consistent, so the same person arrives as multiple records.

Guardrails that stop the relapse

Aim for a few changes that block bad data at the source:

- Make create operations idempotent (store a request or event key and ignore repeats).

- Wrap multi-step writes in a transaction so they succeed or fail together.

- Normalize identifiers before writing (email lowercasing, phone formatting, trimmed IDs).

- Lock down admin paths to use the same validation as the app, not direct updates.

- Add constraints plus monitoring so failures are visible and fixed fast.

If you inherited an AI-built MVP, these issues are common. The database usually isn't the root cause. Loose write paths are.

Example: cleaning up users and orders after an AI-built MVP

A common case is an AI-built signup flow that creates a new user row on every retry. If the same person taps "Sign up" three times, you might end up with three accounts that share an email but have different IDs and partial profile data.

Now add a second issue: after a schema change, some users were deleted (or merged) without updating related tables. Orders still point to the old user_id, so you have orphaned orders that no longer match a real user.

One practical way to fix it without guessing:

- Pick a canonical user for each email (for example, the one with

verified = true, or the earliestcreated_at). - Create an ID mapping table that records

old_user_id->canonical_user_id. - Update orders by joining through the mapping table so every order points to the canonical

user_id. - Only then delete (or archive) the extra user rows.

- Add protections so the mess doesn't come back.

Your mapping table can be as simple as (old_user_id, canonical_user_id), filled from a query that groups by email and chooses the winner. After the update, run quick checks: count users per email, count orders with missing users, and spot-check a few high-value customers.

Finally, lock in integrity. Add a unique constraint on email and a foreign key from orders.user_id to users.id. If you're worried about breaking writes, add them after cleanup and test on a copy of production first.

Quick checklist and next steps

Two things matter at the end: the current data is correct, and it's hard for the same mess to return. Keep notes as you go so someone else can repeat the work later.

Checklist for the cleanup itself:

- A fresh snapshot exists, and you know how to restore it.

- Duplicate rules are written down (matching fields, tie-breakers, what you keep).

- Detection queries were run and saved with timestamps and counts.

- Changes are logged (before/after IDs, merges, deletes, and any manual decisions).

- Cleanup scripts can run on a copy of production and produce the same results.

After the data looks good, lock it in so it stays good:

- Foreign keys and unique constraints are added (or planned) and backed by the right indexes.

- Validation checks pass (row counts, referential integrity, key uniqueness, critical totals).

- Rollback is tested end-to-end on a staging copy.

- Monitoring has a clear owner (alerts, weekly report, or a release gate).

If you're inheriting a broken AI-generated prototype and need a fast, safe path to production, FixMyMess (fixmymess.ai) focuses on diagnosing the codebase, repairing logic and data integrity issues, and hardening the app so the same problems don't reappear.

FAQ

When should I stop building features and clean up the database?

If your app is about to charge money, if you need reliable reporting, or if support is manually fixing records, clean up now. The longer you wait, the more new features and retries will write additional messy data on top, making merges and repairs harder.

What’s the safest first step before I run any UPDATE statements?

Start with a snapshot you can restore quickly, then write down scope and rollback before any updates. If possible, run the full cleanup on a recent production copy in staging first so you can see real edge cases without risking live data.

How do I decide what counts as a duplicate user?

Define duplicates using a clear business key and a keeper rule. A common default is “same normalized email belongs to one user,” then keep the record that is verified or referenced by the most important history like paid orders.

How can I find near-duplicates like email casing or extra spaces?

Normalize the field you’re matching on in your detection queries, like trimming spaces and lowercasing emails, so you catch collisions you’d otherwise miss. Then manually review a small sample of the worst duplicate groups to confirm your rules match real behavior.

Is it better to delete duplicates or merge them?

Don’t delete first if other tables reference the row, because that’s how you break history. Merge by choosing a keeper ID, repointing all foreign keys to the keeper, and only then archiving or deactivating the duplicate rows.

What is an orphaned row, and why does it matter?

An orphan is a child row that points to a parent that doesn’t exist, like an order with a missing user. It may not crash the app, but it quietly breaks totals, exports, and “why does this record look wrong?” support cases.

How do I fix orphaned orders or comments without guessing?

Measure first with a left join check to count and sample orphans, then pick a repair path that matches meaning. Most teams either reassign the child to the correct parent after dedupe, or archive/delete rows that were partial writes or test data.

What constraints should I add to prevent this mess from coming back?

Add constraints after cleanup, not before, so you don’t block your own repair work. A good baseline is unique constraints on real identifiers (like normalized email or provider IDs) and foreign keys for relationships that must not break.

How do I make my cleanup scripts safe to run more than once?

Make scripts repeatable by separating read-only detection from write steps, and by adding guards so re-running doesn’t double-merge or re-archive. Logging counts and keeping a simple mapping table of old IDs to kept IDs makes troubleshooting and reversals much easier.

How do I validate the cleanup worked and the app won’t regress?

Track before-and-after numbers for duplicates and orphan counts, then validate a few critical flows end-to-end, like login and checkout. If you inherited an AI-generated prototype and want fast, safe remediation, FixMyMess focuses on diagnosing the codebase and fixing logic, security, and data integrity issues with human verification.