Migrate SQLite to Postgres: a phased cutover playbook

A practical playbook to migrate SQLite to Postgres in AI-built apps: schema mapping, data types, indexing changes, phased cutovers, and checks.

Why this migration is risky in AI-built apps

AI-generated prototypes often “work” because SQLite is forgiving. It will happily store odd values, accept loose types, and let you get far with minimal setup. Many AI tools also default to SQLite because it is zero-config and easy to ship. The problem is that those early shortcuts become hidden assumptions in your code.

When you migrate SQLite to Postgres, the first breaks usually look small but cascade fast. A query that was fine in SQLite can fail on Postgres because of stricter typing, different date and boolean behavior, and case-sensitive comparisons. Migrations can also fail because SQLite let you add columns or change tables in ways that do not translate cleanly to Postgres.

What tends to break first:

- Authentication and sessions (timestamp handling, unique constraints, case sensitivity)

- “It worked locally” queries (implicit casts, loose GROUP BY behavior)

- Background jobs and imports (bad data that SQLite tolerated)

- Performance (missing indexes that SQLite did not make obvious)

- Deploy scripts (assumptions about file-based DB vs server DB)

Migration is worth it when you need concurrency, real backups, better query planning, safer access controls, or you are outgrowing a single-node setup. It is not worth it if the app is still being thrown away weekly, you do not have stable requirements, or your main bottleneck is product fit, not database limits.

“No downtime surprises” does not mean zero risk. It means you plan for the common failure modes, you can measure progress, and you have a clean rollback path. In practice, you aim for either no user-visible outage or a very short, scheduled window with a clear escape hatch.

This playbook follows a simple arc: inventory what you really have, translate the schema carefully, convert data safely, plan indexes and performance, run a phased cutover with sync, make the app changes people miss, then test and rehearse rollback. If your app was generated by tools like Lovable, Bolt, v0, Cursor, or Replit, teams like FixMyMess often start with a quick codebase diagnosis to surface SQLite-specific assumptions before you touch production data.

What to inventory before touching the database

Before you migrate SQLite to Postgres, get clear on what you actually have. AI-built apps often “work” in a demo, but hide surprises like silent type coercion, ad-hoc SQL, and background jobs that keep writing while you are trying to move data.

Start with a table-by-table map. You want names, row counts, and which tables are growing fast. The biggest tables usually drive your cutover plan because they take the longest to copy and are the most painful to re-index.

If you can, capture a quick snapshot of size and growth:

-- SQLite: approximate quick checks

SELECT name FROM sqlite_master WHERE type='table';

SELECT COUNT(*) FROM your_big_table;

Next, understand traffic. A database migration is rarely blocked by reads. It is blocked by writes you forgot about: webhooks, queues, scheduled tasks, and “helper scripts” someone runs manually.

Here’s a simple inventory checklist that prevents most downtime surprises:

- Tables: row counts, largest tables, and any “hot” tables with frequent updates

- Data flow: which endpoints write, which only read, and which jobs run on a schedule

- Query style: where you use an ORM vs raw SQL strings in the codebase

- SQLite quirks: places relying on loose typing, implicit booleans, or odd date handling

- Config: where connection strings, API keys, and database secrets are stored and injected

Raw SQL is the classic trap. An ORM may adapt queries for Postgres, but a copied SQL snippet from a chat tool might use SQLite-only syntax or assume NULL sorting behavior.

Concrete example: a prototype generated in Replit might store booleans as "true"/"false" text in one table, 0/1 integers in another, and rely on SQLite accepting both. Postgres will force you to choose, and that choice affects queries, indexes, and app logic.

If you inherited a messy AI-generated app, a short codebase diagnosis (the kind FixMyMess does before changes) can uncover these hidden writers and SQLite-specific assumptions before they turn into a failed cutover.

Schema translation that does not surprise you later

When you migrate SQLite to Postgres, the biggest risk is not the data copy. It’s discovering that your app depended on SQLite behaviors you never wrote down.

SQLite often “accepts” a schema that is vague: missing foreign keys, loose column types, and implicit rules in the app code. AI-built apps make this worse because the schema may have been generated quickly, then patched in place.

Make the schema explicit (tables, keys, relationships)

Start by writing a clear map of every table and how rows connect. Don’t rely on what you think the app does - confirm it with the actual schema and real data.

A practical way to translate is to work in this order:

- Define each table’s primary key and whether it should ever change.

- Decide how each relationship works (1:1, 1:many) and add foreign keys on purpose.

- Add the constraints you were relying on implicitly (NOT NULL, UNIQUE, CHECK).

- Handle circular relationships by creating tables first, then adding foreign keys after.

- Keep names consistent (columns like userId vs user_id cause quiet bugs later).

Autoincrement IDs: choose the Postgres version now

In SQLite, INTEGER PRIMARY KEY is a special case that auto-increments. In Postgres you should choose GENERATED BY DEFAULT AS IDENTITY (or ALWAYS) instead of older SERIAL, and document it.

Example: an AI prototype might insert users without an explicit id and assume ids never collide. If you backfill data and forget to reset the identity sequence, the next insert can fail or, worse, reuse ids.

Finally, make your migration script rerunnable. Postgres is stricter, so aim for scripts that are safe to run twice (idempotent): create objects only if missing, and add constraints in a controlled way so a partial run can be resumed without guessing.

Data type mismatches and safe conversions

When you migrate SQLite to Postgres, most scary bugs come from silent type differences. SQLite will happily store "true" in a column you thought was an integer. Postgres will not, and that is a good thing, but it means you need explicit conversions.

The mismatches that cause real breakage

A few patterns show up again and again in AI-built apps:

- Booleans: SQLite apps often use 0/1, "true"/"false", or even empty string. In Postgres, use

booleanand convert with clear rules (for example: only 1 and "true" become true). - Integers stored as text: IDs and counters may be saved as strings. Convert only if every value is clean, otherwise keep text and add a new integer column you backfill safely.

- Nulls and defaults: SQLite can behave loosely with missing values. Postgres will enforce

NOT NULLand defaults. If old rows contain nulls, add the constraint only after you backfill.

Datetime is another trap. SQLite projects often store dates as local-time strings, mixed formats, or epoch seconds. Pick one standard first: timestamptz in UTC is usually the safest. Then convert from one known format at a time and log rows that do not parse. If your app shows “yesterday” for users in different time zones, that is often a sign you are mixing local time with UTC.

JSON fields need a deliberate choice. If you query inside the JSON (filtering by a key, indexing), store it as jsonb. If you only store and retrieve blobs, text can be fine, but you lose validation and query power.

Money and decimals should not use floats. If an AI-generated checkout totals $19.989999, fix it by using numeric(12,2) (or the scale you need) and rounding during conversion.

A practical approach is to run a dry conversion on a copy of production data, count failures by column, and only then lock in the final types and constraints.

Indexing and performance changes to plan for

When you migrate SQLite to Postgres, the app often “works” but feels slower. A big reason is that SQLite and Postgres make different choices about when and how to use indexes.

SQLite can get by with fewer indexes because it runs in-process, with a simple planner and smaller workloads. Postgres is built for concurrency and larger data, but it is strict about statistics, index selectivity, and query shape. If an AI-built app shipped with accidental full-table scans, Postgres will faithfully run them, just at a larger and more visible cost.

Start by choosing indexes from real queries, not guesses. Pull the top read and write queries (login, list pages, search, dashboard counts) and design around them. A quick example: if your app frequently runs WHERE org_id = ? AND created_at >= ? ORDER BY created_at DESC LIMIT 50, a composite index on (org_id, created_at DESC) is usually more useful than two single-column indexes.

Composite indexes and uniqueness

Order matters in Postgres composite indexes. Put the most selective filter first (often org_id or user_id), then the column used for sorting or range scans. Add sort direction when it matches the query.

Also separate the idea of “must be unique” from “helps performance”. A UNIQUE constraint enforces data rules and creates a backing unique index. A standalone unique index can be useful for partial cases, but if it’s really a business rule, model it as a constraint so it’s clear and consistent.

What to check when queries get slow

After the move, focus on:

- Missing composite indexes for common filter + sort patterns

- Wrong data types causing casts (which can block index usage)

- Out-of-date statistics (run ANALYZE after bulk loads)

- Sequential scans on large tables where you expected index scans

- New write overhead from too many indexes on hot tables

If you inherited an AI-generated schema with “index everything” or “index nothing,” this is where a short audit (like FixMyMess does) pays off fast.

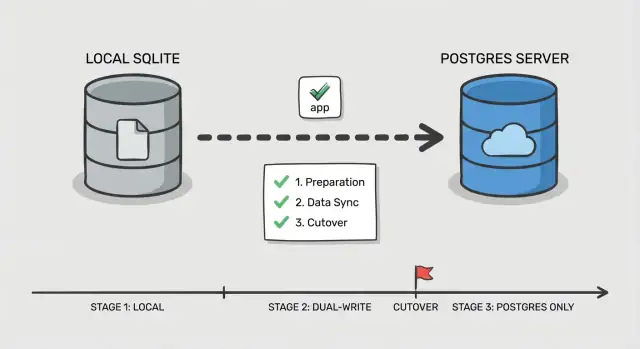

Step-by-step phased cutover plan

A safe cutover is less about one big switch and more about proving each piece works while users keep using the app. This matters even more when you migrate SQLite to Postgres in an AI-built app, where hidden queries and odd edge cases are common.

Phase 0: Decide how you will switch

Pick a simple order: switch reads first, then writes. Reads are easier to validate and easier to roll back. Writes change your source of truth, so treat them as the final step.

Add one control point in the app: a feature flag or config toggle that selects which database handles reads and which handles writes. Keep it boring and explicit so you can flip it quickly during an incident.

Phase 1-5: Execute the cutover in small moves

Before touching traffic, set up Postgres (database, users, roles, and least-privilege access). Make sure your app can connect in the same environment where it runs today.

Then follow a phased flow:

- Bulk copy: snapshot SQLite and load it into Postgres.

- Incremental sync: keep Postgres updated with new changes while the app still uses SQLite for writes.

- Read cutover: route read queries to Postgres, keep writes on SQLite, and watch error rates and slow queries.

- Write cutover: route writes to Postgres, keep a short window where you can still fall back.

- Finalize: stop sync, lock down old credentials, and keep SQLite read-only for a defined period.

Define rollback before you switch anything: what toggle flips back, what data you might lose, and how you will handle it. For example, if your AI-generated app writes user sessions and password resets, decide whether those tables need special handling so a rollback does not break logins.

If you need a second set of eyes, FixMyMess often helps teams rehearse this plan on messy AI-generated codebases before the real cutover.

Keeping data in sync during the transition

When you migrate SQLite to Postgres with a phased cutover, the hard part is not copying the first snapshot. It is keeping changes consistent while real users keep clicking.

Two simple sync patterns (and when to use them)

If the app is low traffic and changes are easy to replay, periodic backfill jobs can work: take an initial copy, then run a scheduled job that copies rows changed since the last run (using updated_at or an append-only events table). This is simple, but it increases the risk of “surprise” differences right before cutover.

If the app is actively used, dual-write is safer: every write goes to both databases for a period of time. It is more work, but it shrinks the gap and makes cutover less stressful.

Keeping IDs consistent

Decide early which system owns primary keys. The simplest rule is: keep the same IDs in Postgres, and never re-number them. If SQLite used integer IDs, set Postgres sequences to start above the current max so new rows do not collide. If you are switching to UUIDs, add a new UUID column first, backfill it, and keep the old ID as a stable external reference until the app is fully moved.

To avoid confusion, define conflict rules up front:

- Pick one source of truth for writes (often Postgres once dual-write starts)

- On mismatch, prefer “latest updated_at wins” only if clocks are reliable

- For money, permissions, and auth, prefer explicit rules over timestamps

- Record every conflict for review

Run both systems in parallel long enough to cover normal usage (often a few days, sometimes a full business cycle). Log enough to spot drift fast: counts per table, checksum samples for hot tables, write failures by endpoint, and a small audit trail of changed IDs. This is where teams often ask FixMyMess to verify dual-write behavior and catch drift before customers do.

App-level changes that commonly get missed

The database swap is only half the job. Many teams migrate the data, point the app at Postgres, and then spend the next day chasing weird errors that never showed up in SQLite.

Connection settings and pooling

SQLite usually means “one file, low concurrency.” Postgres is a server, and it will happily accept too many connections until it suddenly cannot.

If your app uses a pool, set a real limit and timeouts. A common failure pattern after you migrate SQLite to Postgres is background jobs and the web app each opening their own pool, multiplying connections and causing slowdowns that look like “Postgres is slow” when it is really “too many connections.”

Queries that relied on SQLite being forgiving

SQLite often returns results even when SQL is a bit sloppy. Postgres is stricter, and the strictness is usually a good thing.

Watch for comparisons across types (text to numbers), implicit casts, and loose GROUP BY usage. Also check string matching and case rules, because a search that “worked” in SQLite can change behavior if you were relying on accidental case-insensitivity.

Transactions and locking assumptions can flip too. Code that did fine with “write whenever” may now hit deadlocks or contention if it wraps large reads and writes in one long transaction.

Auth and session storage is another quiet trap. If your login sessions, password reset tokens, or refresh tokens live in the database, small differences (timestamps, unique constraints, or cleanup jobs) can cause sudden logouts or broken login flows.

Here’s a quick set of app-side checks that catch most surprises:

- Confirm every app process (web, workers, cron) reads the same DB config and pool limits.

- Replace SQLite-only SQL (like quirks in upserts, date functions, or boolean handling).

- Audit any raw SQL for quoting and parameter style differences.

- Review transaction boundaries and ensure long jobs do not hold locks longer than needed.

- Verify session and token tables, expiry logic, and unique constraints behave the same.

Example: an AI-generated prototype might store sessions in a table with a “createdAt” text column and compare it to “now” as a string. That can appear to work in SQLite, but break expiry checks in Postgres unless you convert it to a real timestamp.

If you inherited an AI-built codebase from tools like Replit or Cursor, this is where services like FixMyMess tend to find the most hidden breakpoints: the data is fine, but the app logic assumed SQLite’s behavior.

Testing, monitoring, and rollback rehearsal

Most downtime surprises happen because the cutover is treated like a one-time event, not a rehearsed procedure. AI-built apps are extra risky here because they often have weak validation, inconsistent queries, and edge cases that only show up with real data.

Start with a repeatable smoke test you can run in minutes on both databases. Keep it small and focused on real user paths, not every feature.

- Sign up/login/logout (including password reset if you have it)

- Create one core record (for example: project, order, or note)

- Edit that record and verify the change is visible everywhere it should be

- Delete it (or soft-delete) and confirm permissions still work

- Run one admin/report screen that joins multiple tables

Next, do a shadow read test. For a slice of traffic or a cron job, read from Postgres and SQLite in parallel, then compare results. Log mismatches with enough context to debug (user id, query inputs, and the primary keys returned). This catches subtle issues like different sort order, NULL handling, case sensitivity, and time zone conversions.

Load test the endpoints that hit your busiest tables, not your whole app. A common case when you migrate SQLite to Postgres is that a query that “worked fine” before now needs a missing index or a better join. Watch for p95 latency and connection pool saturation.

Finally, rehearse rollback once, timed. Write down the exact steps, who runs them, and what “stop the world” looks like (feature flag flip, read-only mode, or traffic drain). Define success metrics before you start: acceptable error rate, p95 latency ceiling, and a mismatch count that must reach zero (or a clearly justified exception list).

Common mistakes and how to avoid them

SQLite is forgiving. Postgres is strict. Many teams get burned because their app worked “somehow” on SQLite, then fails when they migrate SQLite to Postgres.

One common trap is assuming data types will “just work”. SQLite happily stores text in an integer-looking column, or dates as random strings. Postgres will not. Before you move data, scan for columns with mixed values (like "", "N/A", or "0000-00-00") and decide what the real type should be.

Indexes are another classic “later” task that becomes a production fire. SQLite can feel fast on small datasets even without indexes. Postgres might slow down the moment real traffic hits if you forget indexes for foreign keys, common filters, and sort columns.

Cutovers fail when writes switch too early. If you start writing to Postgres before you can detect drift, you will not know which database is “right” when something goes wrong. Add drift checks (row counts, updated-at ranges, checksums on key tables) before you trust the new system.

Also watch for a hidden SQLite file path. AI-built apps often have a default like ./db.sqlite baked into one environment variable or Docker image. Everything looks fine in staging, then production is still writing to the old file.

Long-running migrations are the quiet killer on big tables. A single ALTER TABLE or backfill can lock writes long enough to cause timeouts.

Avoid these with a short pre-flight checklist:

- Audit “messy” columns and normalize values before casting types.

- Create Postgres indexes before the first full load finishes.

- Keep dual-write or change capture off until drift detection is running.

- Search configs and containers for stray SQLite paths.

- Break big backfills into batches with time limits.

If you inherited a shaky AI-generated codebase, teams like FixMyMess often start with a quick audit to surface these risks before the cutover window.

Quick checklist and next steps

If you only remember one thing when you migrate SQLite to Postgres, make it this: most downtime surprises come from small gaps between your plan and what the app actually does in production.

Pre-cutover (get ready)

Do these before you touch production traffic. If any item is uncertain, pause and confirm with a quick test run.

- Confirm backups restore cleanly (not just that they exist) and capture the exact cutover window state.

- Validate the translated schema matches real usage: constraints, defaults, and timestamp behavior.

- Ensure the sync path is already running and stable (dual writes or change capture), with clear ownership of failures.

- Run a short production-like load test on Postgres and verify the top pages or endpoints.

Cutover (switch safely)

The goal is a fast, boring switch with clear signals and a clear exit.

- Use a single, explicit toggle plan (env var, config flag, or router switch) and define who flips it.

- Put monitoring on screen before the switch: error rate, latency, DB connections, and replication/sync lag.

- Have rollback ready and practiced: how to point the app back, and how to handle any writes during the cutover.

After the switch, verify correctness first, then speed. Compare row counts and checksums for key tables, run a few critical queries end-to-end (login, checkout, create/edit flows), and scan logs for new errors like constraint violations or time zone surprises.

Next, tackle performance with focus. Pull the slowest queries you see in production, confirm indexes are used as expected, and fix the few that cause the most user pain.

If your app was generated by tools like Lovable, Bolt, v0, Cursor, or Replit, the database layer often hides messy assumptions (string dates, missing constraints, unsafe queries). FixMyMess offers a free code audit to surface those migration risks early, before you commit to a cutover plan.