Tenant isolation checklist for SaaS prototypes: avoid pitfalls

Use this tenant isolation checklist to spot and fix multi-tenant pitfalls in APIs, storage, background jobs, and analytics before your SaaS prototype ships.

Why tenant isolation breaks in SaaS prototypes

A tenant data leak is simple to picture: a customer logs in, clicks “Projects,” and sees someone else’s project name, invoice, file, or user list. Sometimes it is even smaller, like an autocomplete suggestion that contains another company’s contact, or a dashboard total that quietly includes data from other accounts.

This happens in prototypes because “login works” is not the same as “data is isolated.” Many AI-generated or rushed builds gate pages behind authentication, but they do not consistently apply tenant checks everywhere data is read, written, or processed. One endpoint filters by user ID, another forgets to filter at all. A background job runs without tenant context. A cache key is shared. The UI looks correct, but the underlying rules are uneven.

A few common ways early multi-tenant SaaS apps leak data:

- API endpoints that accept a record ID and return it without verifying it belongs to the caller’s tenant

- Database queries missing a tenant filter in one code path (often admin screens, exports, search)

- Object storage URLs or file paths that are not tenant-scoped

- Background jobs that process “all records” instead of “this tenant’s records”

- Analytics events tagged with the wrong tenant, mixing reports across customers

The cost of a small leak is rarely small. Trust drops fast, support load spikes, and churn follows. If you handle personal data, a leak can also trigger breach notifications, contract issues, or compliance headaches.

Good isolation, for a non-technical founder, means one clear promise: each customer’s data behaves like it lives in its own box, even though you run one app. A practical tenant isolation checklist should cover every place data can move: APIs, database, files, jobs, cache, and analytics. If you inherited a prototype that “mostly works” but feels risky, FixMyMess can audit the codebase and pinpoint where isolation breaks before you onboard more customers.

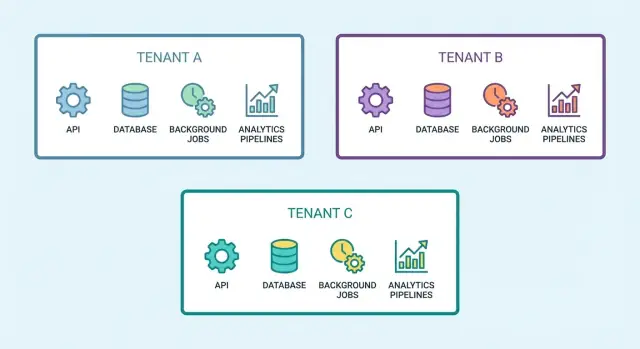

Multi-tenancy basics and the boundaries you must define

Single-tenant means each customer has their own isolated app or database. Multi-tenant means customers share the same app (and often the same database), and your code must guarantee separation. Prototypes often start “mostly working” and then quietly break isolation when a quick feature ships.

The first boundary to define is tenant identity: where does the app learn which tenant this request belongs to? In most SaaS apps, it should come from the authenticated user context (token or session) that is verified by the server. It should not come from anything the client can freely change, like a query string (e.g., ?tenantId=...), a request body field, or a custom header.

The isolation boundaries to set up early

Think of tenant isolation as a set of walls you must build in multiple places:

- Request boundary: every API request resolves a tenant, once, on the server

- Data boundary: every read/write is scoped to that tenant (not just reads)

- Storage boundary: files are separated by tenant and access is checked server-side

- Job boundary: background work runs with an explicit tenant context

- Analytics boundary: events and dashboards never mix tenants

If you are building a tenant isolation checklist, treat each wall as mandatory. Missing just one is enough for a leak.

Shared tables vs separate databases

Shared tables (one database, a tenant_id column) are faster to build and cheaper to run, but need strict guardrails like enforced scoping and constraints. Separate databases (or schemas) can reduce blast radius and make compliance easier, but add operational overhead (migrations, reporting, connection management).

A simple rule: if you expect a small number of high-value tenants with strict requirements, consider stronger physical separation. If you expect many small tenants, shared tables are common, but only if you enforce scoping everywhere, not “most places.”

Where data leaks happen most often

Most tenant data leaks in prototypes are not “hackers breaking in”. They happen when an honest mistake turns a single-tenant assumption into a multi-tenant bug. That is why a tenant isolation checklist is less about fancy attacks and more about removing foot-guns.

First, decide what a “tenant” is in your product (org, workspace, account). Write it down, put it in code comments, and use the same meaning everywhere. Many leaks start when the UI uses “workspace”, the API uses “org”, and the database uses “account_id”.

The most common leak paths look boring, but they ship all the time:

- ID guessing and direct object access: an endpoint loads

/invoices/123without checking that invoice 123 belongs to the caller’s tenant. - Mis-scoped queries: a query filters by user_id but forgets tenant_id, so users who share an email domain or role see extra rows.

- Shared storage buckets or folders: files are stored under predictable keys, and access rules do not include tenant context.

- Background jobs without tenant context: a job runs “send weekly report” for the wrong tenant because the queue payload did not include tenant_id.

- Admin and support shortcuts: “temporary” endpoints, debug panels, or exports bypass the normal authorization path.

Indirect leaks are even easier to miss because no one “sees” raw records. Watch features like search, autocomplete, analytics dashboards, and CSV exports. A single count, top result, or “recent items” list can reveal that another tenant has a customer named X or a project titled Y.

If you are inheriting an AI-generated prototype, treat every query, job, and storage access as suspect until you can point to one clear tenant boundary check.

How to enforce isolation in your APIs (step by step)

Tenant isolation usually fails in APIs because tenant context is handled “sometimes” instead of “always”. The safest approach is to treat tenant context like authentication: one clear source of truth, applied on every request.

A repeatable API pattern

Start by deciding where tenant context is authoritative. Pick exactly one: token claims (common with JWT) or server-side session. Everything else is just input.

Then implement a single guard that runs for every endpoint:

- Read the authenticated user and the tenant from your chosen source of truth.

- Ignore any tenantId coming from the client (body, query string, headers). If you need it for routing, treat it as a hint and compare it to the authenticated tenant.

- Run a consistent authorization check (user belongs to tenant, role allowed for action).

- Pass tenant context into service methods, not just controllers. Avoid “global” helpers that can accidentally run without tenant.

- Return the same error shape for “not found” and “not allowed” when tenant mismatch could reveal data (for example, respond as if the record does not exist).

A concrete example: an endpoint like GET /invoices/:id looks harmless, but if the handler loads Invoice.findById(id) before checking tenant, you can leak data by guessing IDs. The fix is to scope the query: “find invoice by id AND tenant”. Do the same for updates and deletes.

Quick two-tenant test

While building, keep two test tenants open in separate browser profiles. Create similar records in both, then try copy-pasting IDs between tenants. If anything shows up, your tenant isolation checklist just found a real bug.

If you inherited an AI-generated prototype, this is a common failure mode FixMyMess sees in audits: tenant context exists, but it is not enforced consistently across endpoints.

Database isolation: queries, constraints, and guardrails

Most tenant leaks happen because the database accepts a query that “looks right” but forgot one filter. If you want a practical tenant isolation checklist, start here: make it hard to run an unscoped query, even by accident.

First, assume every read path will be used for lists and search. Those are the places where developers often write one reusable query and forget to include the tenant condition. A good rule is: if a table is tenant-owned, every query must include tenant_id, including counts, exports, autocomplete, and “recent items”.

Guardrails that catch mistakes

App code checks help, but database rules catch mistakes when code changes. Add tenant_id to every tenant-owned table and enforce it with constraints and indexes. For example, use composite uniqueness like (tenant_id, email) for users, and ensure foreign keys include tenant scope (or validate tenant match in triggers when composite FKs are not practical).

Quick guardrails to add early:

- Add

NOT NULL tenant_idon tenant-owned tables. - Use composite indexes that start with

tenant_idto make scoped queries fast. - Use composite unique constraints to avoid cross-tenant collisions.

- Block “default tenant” fallbacks in production.

Row-level security (RLS) and “global” tables

Row-level security can help when multiple services or query paths touch the same tables. It works best when every connection sets a tenant context and you can test it reliably. It is not a substitute for good authorization, but it reduces blast radius when someone forgets a filter.

For “global” tables like plans or templates, separate truly global data from tenant overrides. A common safe pattern is: global rows have no tenant_id, tenant customizations live in a different table that is tenant-owned.

Finally, plan admin support access. Use a separate role or endpoint, require explicit tenant selection, and log every admin read and write with who, when, and which tenant. If you inherited an AI-generated schema where this is messy, FixMyMess can audit queries and constraints quickly and point out where isolation can break.

Files and object storage: prevent accidental cross-tenant access

Files are a common place where prototypes leak data. Code often “works” with a single bucket and a single folder, then quietly breaks isolation when a second tenant uploads a file with the same name, or when a shared URL gets forwarded.

Start with one rule: every stored object needs an unambiguous tenant boundary. The simplest pattern is a required tenant prefix in the storage key (for example, tenants/<tenant_id>/...) and the app should refuse to read or write anything that does not match the current tenant.

Avoid public buckets and long-lived public URLs by default. If you need sharing, prefer short-lived signed URLs that are generated only after your server verifies both identity and tenant membership. Never trust a client-provided file path or object key.

Your download and preview endpoints are the real gatekeepers. A common bug: GET /files/:id loads a DB record by id, then returns the file, but the query forgets WHERE tenant_id = ?. One missing filter turns into a cross-tenant breach. Treat this as part of your tenant isolation checklist.

Also watch metadata. Filenames, EXIF data, PDF properties, or “uploaded_by” strings can expose tenant names, internal IDs, or email addresses when files are shared.

A quick audit you can run today:

- Confirm every object key includes a tenant prefix and it is enforced server-side.

- Check every file lookup includes

tenant_idin the query and in authorization. - Ensure shared access uses short-lived signed URLs, not public objects.

- Strip or rewrite sensitive metadata on upload (especially images and PDFs).

- Define tenant-level retention and deletion rules, and verify full deletion on offboarding.

If you inherited an AI-generated prototype (Lovable/Bolt/v0/Cursor/Replit), FixMyMess often finds storage rules that look right in code but are not consistently enforced in production.

Background jobs and queues: keeping tenant context intact

Background work is where tenant isolation quietly breaks. The API request had the tenant ID and the right permissions, but once you hand work to a queue, that context can disappear. Then a worker grabs a job, runs with “system” access, and touches the wrong tenant’s data.

A simple rule helps: every job must carry its tenant context in the payload at creation time. That usually means tenant_id plus the minimum identifiers needed (like user_id or invoice_id), and nothing that can be “looked up later” without checks.

Never rely on “current user” inside a worker. Workers do not have a real logged-in user, and any shared global state (like a cached user object or default database schema) can point to the last job that ran. Instead, the worker should explicitly set tenant scope at the start of the job and validate it before doing anything else.

Retries can also cause leaks. If a job fails and is retried, make sure the retry payload still includes the tenant ID and that the worker re-applies tenant scoping on every attempt. The same applies to dead-letter queues: when you inspect or replay failed jobs, tenant context must still be present and visible.

Shared queues are fine, but mixed-tenant logs are risky. If your worker logs request bodies, SQL errors, or full object dumps, you can accidentally spill one tenant’s data into logs that other staff (or tools) can see. Log with tenant IDs and short identifiers, not full records.

Quick checks that catch most issues:

- Create a job and confirm

tenant_idis stored in the job payload and shown in worker logs. - In the worker, fail fast if

tenant_idis missing or does not match the fetched record’s tenant. - On retry and dead-letter handling, verify tenant scoping is re-applied and not “remembered.”

- Add per-tenant rate limits or queue fairness so one noisy tenant cannot starve others.

If you inherited an AI-generated prototype, job workers are often where tenant context is implicit and unsafe. FixMyMess can audit the queue and worker paths and repair isolation issues fast, before they turn into a data incident.

Caching, sessions, and notifications: the hidden cross-tenant risks

Caching and sessions are easy to “set and forget” in prototypes. That’s why they’re a common reason a tenant isolation checklist fails in real life. One tenant’s request warms the cache, and the next tenant gets the same response.

A simple example: your API returns /settings for the current user. You cache it under settings for 5 minutes. Tenant A hits it first, then Tenant B sees Tenant A’s logo, plan, or even billing email. Nothing “hacked” you - it’s just a tenant-blind cache key.

Cache keys, invalidation, and “shared” objects

Make cache identity match data identity. If the data is tenant-scoped, the cache must be tenant-scoped too, including invalidation.

- Include

tenant_id(and often user role) in cache keys for API responses. - Invalidate by tenant when tenant data changes, not only by endpoint.

- Be careful with “global” caches (feature flags, templates) that quietly contain tenant-specific fields.

- Prefer caching IDs and re-checking access on read when data is sensitive.

Sessions, notifications, and logs

Sessions can also cross borders if you don’t bind them tightly. A session token should map to a user and a tenant, and every request should confirm both.

Before you ship, spot-check these areas:

- Session storage prevents replay across tenants (token -> user_id + tenant_id, verified on every request).

- Password resets, invites, and magic links include tenant context and expire quickly.

- Email, SMS, and in-app notifications verify the recipient belongs to the tenant at send time.

- Logs never store secrets (API keys, tokens) or sensitive tenant data “for debugging”.

If you inherited an AI-generated prototype, these issues often hide in glue code. FixMyMess can run a quick audit to find tenant-blind caches, weak sessions, and unsafe notification paths before production.

Example: a simple tenant data leak and how it happens

A small agency and a local bakery sign up for the same SaaS prototype. Both create “clients” in the app and use a simple list page to find them.

The prototype stores records like clients(id, tenant_id, name, email). The API endpoint looks harmless: GET /api/clients?search=ann.

The bug: the query filters by the search term, but forgets the tenant.

So the agency searches for “Ann” and gets back the bakery’s “Ann Smith” too. No one notices at first because it only happens when names overlap.

It gets worse in places that reuse the same query. A CSV export pulls “all matching clients” and includes cross-tenant rows. A background job that sends “weekly client summary” emails uses the same logic and attaches the wrong records. A dashboard widget counts “new clients this week” across everyone, so the bakery sees inflated numbers and the agency sees a drop that makes no sense.

A fast fix is adding a tenant filter to that one endpoint. That stops the immediate leak, but it is fragile because the next endpoint might repeat the mistake.

A proper fix usually has two layers:

- Make tenant scope automatic in the API (derive

tenant_idfrom the authenticated user, not from request params). - Add database guardrails (row-level security or a required tenant constraint so unscoped queries fail).

- Ensure exports, emails, and analytics queries use the same scoped access path.

To prevent regressions, keep one repeatable test that fails loudly: create two tenants, insert a record with the same name in both, call the list endpoint as Tenant A, and assert every returned row has Tenant A’s tenant_id. Run it for the API and for the export job.

If you inherited an AI-generated prototype, this exact pattern is common. Teams like FixMyMess often find the leak in one endpoint, then trace it to shared query helpers and background jobs so it gets fixed once, everywhere.

Audit checklist: quick checks across the whole stack

A tenant isolation checklist is most useful when it forces you to look for the same mistake in different places: “tenant id missing or ignored.” Run this audit whenever you add a new feature, a new endpoint, or a new background task.

Start with these fast checks:

- APIs: The tenant must be derived server-side (from the user session, token, or subdomain), not accepted from the client as a trusted field. Every route that reads or writes data should enforce tenant scope, including “admin” and internal endpoints.

- Database: Every tenant-owned table has a tenant key, and you can’t insert a row without it. Queries are always scoped by tenant, and there is a guardrail (constraints, policies, or tests) that fails loudly when tenant scope is missing.

- Files and object storage: Paths are per-tenant (for example, a tenant prefix), access is signed or otherwise gated, and “public by default” is off. Don’t rely on the UI to hide other tenants’ files.

- Background jobs: Jobs carry tenant context explicitly, validate it before work starts, and log safely (no secrets, no raw customer data). Retries should not lose tenant context.

- Analytics and exports: Events include tenant identifiers, dashboards are filtered by tenant, and exports (CSV, emails, “download all”) cannot include other tenants’ data.

10-minute smoke test

Create two tenants: “Acme” and “Beta.” Create one record in each (a user, invoice, file, and one analytics event). Then try simple attacks: change an ID in a URL, replay an API call while logged into the other tenant, or run an export from each tenant.

If you find even one cross-tenant read, treat it as a production blocker. Teams often ask FixMyMess to do a quick isolation audit on AI-generated prototypes because these gaps hide in copy-pasted routes, job handlers, and “temporary” admin screens.

Common multi-tenant traps to avoid

Most tenant leaks do not come from one big mistake. They come from small shortcuts that feel harmless in a prototype, then quietly ship to production.

Traps that cause real leaks

Watch for these patterns when you run your tenant isolation checklist:

- Accepting a tenantId from the UI, query string, or request body, then using it directly in queries. The server should derive tenant context from the authenticated user or token, not from user input.

- Securing the main CRUD endpoints but forgetting the “side” routes like search, count, export, autocomplete, and webhook handlers. These often query wider tables and are easy to miss in reviews.

- Keeping a shared “admin” endpoint and assuming it is safe because it is not in the UI. Without strict role checks and a clear allowed tenant scope, it becomes a universal backdoor.

- Using caching for list endpoints without a tenant-aware cache key. One cached response can be served to many tenants, especially when pagination and filters are involved.

- Letting analytics mix tenants, then treating dashboards as the source of truth. Once mixed data is in reports, people make decisions from it, and it is hard to clean up.

A simple example: your API correctly scopes /invoices by tenant, but /invoices/export only checks “is logged in” and runs a broad query. A single customer clicks Export and receives rows from other companies.

If you inherited an AI-generated prototype, these issues show up a lot because code is duplicated and “almost the same” across routes. FixMyMess often sees one endpoint updated with tenant scoping while three similar endpoints still leak data.

A good rule: every request, every query, every cache entry, and every event should carry tenant context explicitly, and fail closed when it is missing.

Next steps: harden isolation before you go to production

Before you onboard real customers, decide how you will fix isolation: patch the prototype you have, or rebuild only the risky parts (auth, data access layer, background jobs). Patching is faster when the architecture is mostly sound. Rebuilding is safer when tenant checks are scattered across the code, or when the app mixes “who the user is” with “which tenant they belong to.”

A practical way to move forward is to treat isolation like a release blocker and add a tiny regression plan that you can run every time you change anything sensitive. Even a simple “two-tenant test suite” catches most leaks.

A simple 1-hour hardening plan

Work through these steps in order:

- Pick two test tenants (Tenant A and Tenant B) and create identical data in both.

- Run your core flows while logged into Tenant A and try to access Tenant B by changing IDs in the URL, request body, and filters.

- Trigger background jobs (emails, exports, webhooks) and confirm they only touch the correct tenant.

- Check object storage keys and signed URLs to ensure they are tenant-scoped.

- Verify analytics events include tenant context and cannot be queried across tenants by default.

Schedule a short isolation audit right before launch. The goal is not perfection, it is confidence that your highest-risk paths are covered and that your “tenant isolation checklist” is actually enforced by code, not conventions.

If your prototype was generated by tools like Lovable, Bolt, v0, Cursor, or Replit, assume tenant boundaries were not designed carefully. FixMyMess can run a free code audit to map where tenant context is lost, then harden auth, data access, and deployment readiness so your first real customers do not become your test suite.