Untangle spaghetti database relationships with a clear redesign

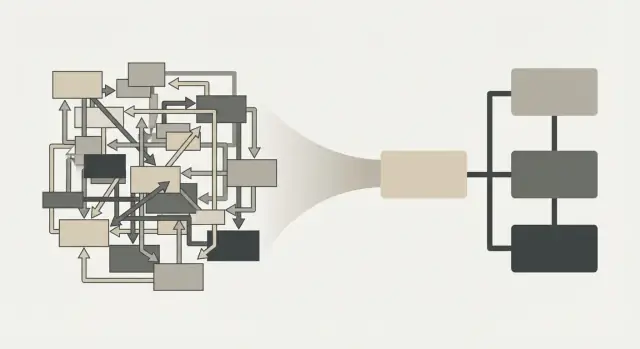

Untangle spaghetti database relationships by spotting circular dependencies, overloaded tables, and unclear ownership, then redesigning with simple rules.

What spaghetti relationships look like in practice

Spaghetti relationships in a database mean your tables are tied together in messy, surprising ways. Instead of a few clear paths (like users -> orders -> payments), you get a web of cross-links where many tables point to many others, rules are inconsistent, and no one can explain why a relationship exists. The schema technically works, but it’s hard to reason about.

You feel it in day-to-day work. A small change (add a field, tweak a status, split a feature) turns into a chain reaction: one migration breaks a report, a fix for one bug causes another, and simple queries need six joins plus weird filters to avoid duplicates. People start copying queries from old tickets because understanding them from scratch takes too long.

Early warning signs (even if you’re not a database expert)

You can often spot the mess without reading every table. Watch for a few patterns:

- The same concept shows up in multiple places (for example, both

customer_idandbuyer_id, or three differentstatuscolumns). - Tables have lots of nullable columns that only apply in special cases (a do-everything table).

- You see join tables for things that shouldn’t be many-to-many, or many-to-many relations used as a shortcut.

- Deleting a record is scary because you don’t know what else it will break.

- People aren’t sure who “owns” a piece of data, so they store it wherever it’s convenient.

A simple example: you have users, orders, invoices, payments, and tickets. In a clean setup, each has a clear role. In a spaghetti setup, tickets has an order_id, payments has a ticket_id, users has a last_invoice_id, and invoices also point back to users for “current plan.” Now one billing bug involves four tables and two different ideas of what “current” means.

The goal here is practical cleanup: how to recognize circular dependencies, overloaded tables, and unclear ownership, then redesign toward clarity and maintainability. No deep database theory, no normalization debates. You want a schema a new teammate can read, query, and change without fear.

Make a quick map of the current schema

Before you redesign anything, get a simple picture of what you have. The goal isn’t a perfect ER diagram. It’s a shared map that helps your team talk about the same tables in the same way.

Start by listing every table and writing one plain sentence for what it represents. If you can’t describe a table without using another table’s name, treat that as a warning sign.

Then describe relationships in everyday words: “a user has many orders,” “an order has many items,” “a product can be in many orders.” Keep it simple. You’re trying to see intent and shape, not every edge case.

A 30-minute mapping pass that actually helps

Time-box it and capture only what you need to make decisions:

- Table purpose: one sentence, plus the top 3 columns that make it unique

- Key relationships: what it points to (foreign keys) and what points to it

- Hot spots: tables touched by many features, screens, jobs, or services

- Write vs read: where the app inserts/updates vs where it only selects

- Naming clashes: tables or columns that sound alike but mean different things

After that, mark your hot spots clearly. A “hot” table isn’t automatically bad, but it’s where spaghetti often starts: quick fixes land there, extra columns pile up, and every new feature depends on it.

Also capture data flow. Many messy schemas come from not knowing the source of truth. For each table, note who writes it (signup flow, admin panel, background job, import script) and who only reads it (dashboards, reporting, search). If a table is written in five places, expect inconsistent rules and surprising bugs.

Finally, create a tiny glossary. Pick the 5-10 words that cause arguments: “account,” “user,” “customer,” “workspace,” “org,” “member.” Write one sentence for each. For example: “Account = billing entity. User = person who logs in. Customer = the account’s paying company.” This prevents redesign debates from turning into language confusion.

If you inherited an AI-generated prototype, this map is often where you first notice duplicates like users, app_users, and customers all trying to mean the same thing.

How to identify circular dependencies

A circular dependency happens when tables depend on each other in a loop. The simplest version is A points to B, and B points back to A. In real apps, it often becomes A -> B -> C -> A, and nobody can explain which record is the parent.

A common example: you have users and teams. A user belongs to a team (users.team_id). Someone also adds “team owner” as a foreign key back to users (teams.owner_user_id). Now inserting the first team and first owner gets tricky: which one must exist first?

Cycles show up in a few places:

- Self-references like

categories.parent_id, especially when other tables also point tocategoriesand you allow deep nesting. - Join tables that quietly become “real” entities, then start pointing back to both sides plus extra tables (roles, permissions, invitations).

- Shared lookup or status tables that grow into a hub. If

statusesstarts referencingordersfor “current order status,” you’ve built a loop.

You can detect circles two ways: by reading foreign keys and by watching app behavior.

From foreign keys, draw a quick arrow for each FK (child -> parent). If you can follow arrows and come back to where you started, you have a cycle.

In app behavior, cycles usually look like this:

- You can’t create records without hacks (nullable FKs “just for now,” then never fixed).

- Deleting a record explodes into blocked deletes, or worse, surprise cascades.

- Updates require multi-step transactions because each table needs the other to be valid.

- You see “temporary rows” or placeholder IDs used during signup, checkout, or onboarding.

Circular dependencies are painful because they hide ownership. It becomes hard to reason about what should exist first, what can be deleted safely, and what data is truly optional.

How to spot overloaded tables

An overloaded table tries to represent more than one real-world thing. It becomes a junk drawer: new fields get added because “it’s kind of related,” until the table holds several different meanings at once.

A quick gut-check: if you can’t describe what a single row represents in one clear sentence, the table is probably overloaded.

Fast schema clues

You can often spot the problem just by scanning the columns. Overloaded tables tend to have lots of nullable fields, clear clusters of unrelated columns (billing next to shipping next to support), and repeated patterns like *_status, *_date, *_note that look like separate workflows crammed into one row. Another giveaway is a table with foreign keys into unrelated parts of the app (payments, marketing, support, inventory) all from one place.

None of these alone prove there’s a problem, but when several show up together, it’s a strong signal.

Clues hiding in the data

The data usually tells the story more clearly than the schema.

If you query the table and see record types mixed together, you’ll notice inconsistent values and rules. For example, some rows use status = 'paid', others use status = 'closed', and others leave it blank because that status doesn’t apply to that kind of row.

Another smell is a table where “type fields” are everywhere: record_type, source_type, owner_type, target_type. That often means the table is acting as multiple tables in disguise.

Overloaded tables are bug factories because different parts of the app make different assumptions about what a row is. Reporting becomes unreliable too: two teams can run “total active records” and get different numbers because each filters a different subset of columns.

How to decide what to split

When you redesign, splits usually fall into three buckets:

- Split by concept when the table holds different nouns (for example, mixing “customer,” “vendor,” and “employee” details).

- Split by lifecycle when one row tries to cover stages that should be separate (draft vs submitted vs fulfilled, each with different required fields).

- Split by actor when different teams or systems own different parts of the record (finance-owned payment details vs support-owned ticket details).

A practical test: list the top 5 queries and writes that touch the table. If they naturally fall into separate groups with different rules and required fields, you’ve found a clean split point.

Find unclear ownership and duplicated concepts

A lot of pain in database refactoring comes from one simple problem: nobody knows which table is the source of truth.

Ownership means a table is the place where a fact is created and updated, and every other table treats it as a read-only reference (or a clearly labeled cache). When ownership is clear, bugs are easier to fix because you know where changes should happen. When it’s unclear, small edits turn into surprises because the same “truth” exists in multiple places.

Where ownership usually gets messy

Ownership breaks down after fast prototype work, especially when people copy patterns from other features.

Look for these patterns:

- Two tables that both look like “the customer” (for example,

customersandclient_accounts) and both get updated by the app. - A shared “profile” table used by users, admins, and vendors, where different code paths overwrite each other’s fields.

- Status or settings stored in multiple places (a column in

users, plus auser_settingsrow, plus JSON inmetadata). - One table that stores business facts and UI convenience fields together (billing details mixed with display name and avatar).

- Foreign keys that point both ways because neither side “owns” the relationship.

Spot duplicated concepts before you rename anything

Duplicated concepts are sneaky because the names differ. A fast way to find them is to list key business nouns (user, account, customer, org, order) and then search your schema for all tables and columns that represent them.

Example: your app has users.email and also contacts.email, and both are edited during sign-up. Now you have to decide which one drives login, notifications, and billing. If the app can write to both, you will get drift.

The fix is to pick one source of truth and make responsibilities explicit: one table is allowed to write the canonical value; other tables can read it or cache it, but caches should be clearly labeled and easy to rebuild.

Simple naming rules reduce ambiguity quickly:

- Use one word for one concept (

customervsclient: pick one). - Put canonical fields in the owned table; avoid duplicating them elsewhere.

- Name references consistently (

customer_id, notcustIdin one table andclient_idin another). - If you must cache, say so (

customer_email_cached).

Redesign principles that keep relationships readable

If you want to untangle spaghetti database relationships, make the important things obvious: what the system is about, what owns what, and what can be safely deleted or changed later.

Start with the few entities everything depends on

Pick the small set of core entities that must exist before anything else can work. These are usually things like User, Account, Organization, Product, Order, or Invoice.

If your schema makes a core entity depend on optional records (like logs, settings, or tags), you end up with fragile inserts and confusing deletes.

A quick test: if a table can’t be created without joining three other tables, it probably isn’t a core entity. It may be a relationship table or a detail table instead.

Keep relationships explicit and predictable

Good schemas feel boring in the best way. A few habits make a big difference.

Separate reference data (small, slow-changing lists like countries, statuses, plan types) from transactional data (orders, payments, events). Reference tables should rarely depend on transactional tables.

Use clear join tables for many-to-many. If Users can belong to many Teams, prefer a UserTeam table with just keys and a couple of fields (role, created_at) instead of stuffing arrays or duplicate columns into both sides.

Be consistent with primary keys and foreign keys. Pick one key style (UUID or integer) and use it everywhere unless there’s a strong reason not to. Mixing styles makes joins and debugging harder.

Name columns like they act. Use team_id when it points to Teams. Avoid generic names like ref_id or data_id that hide ownership.

Document lifecycle in plain words: what gets created first, what can be created later, and what must never be deleted while other records exist.

Here’s a concrete scenario: if Order needs User, and User needs latest_order_id to exist, you have a loop that will cause broken sign-ups and partial writes. The fix is often to remove “latest_*” foreign keys from the parent and compute them with a query (or use a separate summary table that doesn’t block inserts).

Step by step: refactor without breaking the app

The safest way to untangle spaghetti database relationships is to treat it like surgery: small area, clear plan, and checks after every change. Pick one workflow you can describe in a sentence, like “create an order” or “invite a teammate,” instead of trying to fix the whole schema at once.

A safe migration pattern

Start by designing the new tables next to the old ones. Keep the current tables working while you add cleaner ones with clear names, keys, and ownership. For example, if one table mixes user profile fields, auth tokens, and billing status, split the new design so each concept has one home.

Then move data and behavior in stages:

- Choose a small target area and write down the exact queries the feature uses today.

- Create the new tables alongside the old ones (don’t delete or rename anything yet).

- Backfill data from old to new, then validate counts and key rules (unique keys, foreign keys, not-null columns) with simple queries.

After backfill, migrate reads before writes. Switching reads first lets you see if the app still shows the same results while the old write path keeps data flowing. A simple approach is to add a feature flag or config toggle so you can turn the new reads on and off during testing.

Once reads are stable, move writes carefully:

- Switch writes to the new tables, and keep a short period where you also write to the old tables if rollback risk is high.

- Remove dead code paths and old columns only after you’re sure nothing depends on them.

Lock it in so it stays clean

Don’t stop at structure. Add constraints that match the rules you actually mean (for example, “an order must have exactly one customer” or “a membership must be unique per user and workspace”).

Add small checks too: a migration-time script that compares row counts, a daily query that looks for orphan rows, or a basic test around the workflow you just touched.

Example: cleaning up a messy orders and users schema

A common case looks like this: checkout works in dev, but in production you see random “user not found” errors, duplicate charges, and orders that show the wrong address. The schema usually has familiar tables (users, orders, payments), but the relationships are tangled enough that small changes break something else.

Here’s a typical mess:

- A single table like

user_ordersthat mixes user info, billing fields, shipping address, order totals, and payment status. users.last_order_idpoints toorders.id, whileorders.user_idpoints back tousers.id.orders.payment_idpoints topayments.id, butpayments.order_idalso points toorders.id.

That setup creates two problems at once.

First, you get circular dependencies: you can’t insert an order without a payment, and you can’t insert a payment without an order, so the app uses temporary rows or weird update sequences.

Second, the table is overloaded: every update to a user email or address risks rewriting old orders (or leaving old orders inconsistent).

A cleaner redesign is usually a split plus clear ownership:

usersowns identity (login email, name, auth IDs).addressesis owned byusers(many addresses per user).ordersis owned byusers(one user has many orders).order_itemsis owned byorders(one order has many items).paymentsis owned byorders(one order can have one or many payment attempts).

Now the insert flow is simple: create the order, add items, then create a payment attempt. No placeholder IDs. No last_order_id column needed because “last order” is a query.

In app code terms, queries get clearer: checkout stops doing cross-table updates to keep everything in sync, and order history becomes a straightforward join from users to orders to items.

Common mistakes that make the mess worse

The fastest way to get stuck again is to “clean up” the schema without a plan for how the app and data will move with it. Most failures aren’t about SQL skills. They happen because small changes ripple into jobs, reports, and edge cases nobody remembered.

Changes that feel tidy but create new breakage

A classic mistake is splitting a table because it looks too big, then pushing the new tables live without a migration plan. If the old and new tables both get written to for a while, you get data drift: two sources of truth that never fully match. The app seems fine until a refund, a support case, or a month-end report exposes the mismatch.

Another common problem is removing columns too early. Background jobs, exports, dashboards, and admin screens often depend on legacy fields long after the main product code stops using them. Deleting them before you have a full inventory turns a schema cleanup into a production incident.

Other mistakes that reliably make things worse:

- Adding more “type” fields (

user_type,order_type,entity_type) instead of modeling real relationships with clear tables and foreign keys. - Ignoring constraints and trusting app code only, which lets bad data slip in during imports, scripts, retries, or future features.

- Renaming concepts (“customer” to “account”) without agreeing on definitions, so different teams use the same word to mean different things.

A quick example of how this goes wrong

Imagine an overloaded users table that also stores billing fields, org membership, and lead info. Someone splits it into users, customers, and leads, but doesn’t backfill consistently and doesn’t lock down which table owns the email. Now two tables accept updates to the same email, and support tooling reads the wrong one. The schema looks cleaner on paper, but ownership got less clear.

A safer mindset is: treat schema changes like product changes. Make ownership explicit, add constraints early, migrate data in steps, and keep old fields until you have proof nothing depends on them.

Quick checklist and practical next steps

When a schema feels tangled, you don’t need a big rewrite to make progress. Start with a short set of checks that shows where the confusion is coming from, then pick one small refactor you can finish safely.

Quick checks (find the mess)

Look for the patterns that create spaghetti relationships fast:

- Circular links: table A depends on B, B depends on C, and C depends on A (often through helper tables).

- Duplicated concepts: the same real-world thing stored in multiple places (for example, both

customer_idandbuyer_idmeaning the same person). - Overloaded tables: one table doing many jobs (orders + payments + shipping + support notes jammed together).

- Confusing source of truth: two tables both claim ownership (for example, both

usersandaccountsstore email and status). - Weak constraints: missing foreign keys, missing unique constraints, and “anything goes” columns that hide mistakes.

After you spot one or two of these, pick a single area (like payments or user identity) and treat it as one mini-project.

Safety checks (don’t lose data)

Before changing structure, plan how you’ll prove nothing broke:

- Take a backup and confirm you can restore it.

- Write a rollback plan for each change (even if it’s just “keep old columns until verified”).

- Backfill in steps: create new fields or tables first, then copy data, then switch reads, then switch writes.

- Verify after backfills: row counts, sums, and spot checks on real records (including edge cases).

- Add basic monitoring: watch error rates and failed queries during the rollout window.

Maintainability comes from small, clear decisions. Give each table a single owner (the home for that concept), choose consistent names, and enforce rules with constraints so problems fail early instead of spreading quietly.

If you’re dealing with a broken AI-generated app and the schema keeps fighting you, treat the app code and schema as one system. Refactor one workflow end-to-end (schema + queries + tests), then move to the next.

If you want a fast second opinion before rewriting large parts, FixMyMess at fixmymess.ai does free code audits for AI-generated codebases and helps remediate issues like tangled schemas, broken logic, and security gaps, typically within 48-72 hours. "}