Webhook reliability: stop missing Stripe, GitHub, Slack events

Webhook reliability stops missed or duplicated Stripe, GitHub, and Slack events by adding signatures, idempotency, retries, and dead-letter handling.

Why webhook handlers fail in real life

A webhook is a callback: one system sends your server an HTTP request when something happens, like a payment, a push, or a new message.

On paper, that sounds clean. In production, reliability breaks down because networks are messy and providers protect themselves with retries. The same event can show up twice, show up late, or look like it never arrived.

Teams usually run into a few recurring failure modes:

- Missing events: your endpoint timed out, crashed, or was briefly down.

- Duplicates: the provider retried and you processed the same event again.

- Out-of-order delivery: event B arrives before event A, even if A happened first.

- Partial processing: you wrote to the database, then failed before responding, and got retried.

Most providers only promise "at least once" delivery, not "exactly once." They’ll try hard to deliver, but they can’t guarantee perfect timing, perfect ordering, or a single delivery.

So the goal isn’t to make webhooks behave perfectly. The goal is to make your results correct even when requests arrive twice, arrive late, or arrive out of order. The rest of this guide focuses on four defenses that cover most real-world failures: idempotency, signature verification, sensible retries, and a dead-letter path so failures become visible instead of silent.

What Stripe, GitHub, and Slack will do to your endpoint

Webhook providers are polite, but they’re not patient. They’ll send an event, wait a short time, and if your endpoint doesn’t respond the way they expect, they’ll try again. That’s normal behavior.

Assume these will happen sooner or later:

- Timeouts: your endpoint takes too long, so they treat it as failed.

- Retries: they resend the same event, sometimes multiple times.

- Bursts: a quiet day turns into 200 events in a minute.

- Temporary failures: your server returns a 500, a deploy restarts a worker, or DNS has a hiccup.

- Delivery delays: events arrive minutes later than you expect.

Duplicate delivery surprises a lot of teams. Even if your code did the right thing, the provider may not know it. If your handler times out, returns a non-2xx, or closes the connection early, the same event can come back. If you treat every delivery as new, you can double-charge, double-upgrade, send duplicate emails, or create duplicate records.

Ordering also isn’t guaranteed. You might see "subscription.updated" before "subscription.created," or a Slack message edit before the original message create, depending on retries and network paths. If your logic assumes a clean sequence, you can overwrite newer data with older data.

This gets worse when your handler depends on slow downstream work like a database write, sending email, or calling another API. A realistic failure looks like this: your code waits on an email provider for 8 seconds, the webhook sender times out at 5 seconds, retries, and now two requests race to update the same record.

A good handler treats webhooks like unreliable deliveries: accept fast, verify, dedupe, and process in a controlled way.

Idempotency: the one fix that prevents double processing

Idempotency means this: if the same webhook event hits your server twice (or ten times), your system ends up in the same state as if you handled it once. That matters because retries are normal.

In practice, idempotency is deduping with memory. When an event arrives, you check whether you already processed it. If yes, you return success and do nothing else. If no, you process it and record that you did.

What you need to dedupe

You don’t need much, but you do need something stable:

- Provider event ID (best when available)

- Provider name (Stripe vs GitHub vs Slack)

- When you first saw it (useful for cleanup and debugging)

- Processing status (received, processed, failed)

Store this somewhere durable. A database table is the safest default. A cache with a TTL can work for low-risk events, but it can forget during restarts or evictions. For money or access changes, treat the dedupe record as part of your data.

How long should you keep keys? Keep them longer than the provider retry window and longer than your own delayed retries. Many teams keep 7 to 30 days, then expire old records.

Side effects to protect

Idempotency shields your highest-risk actions: charging twice, sending duplicate emails, upgrading a role twice, issuing a double refund, or creating duplicate tickets. If you do only one reliability improvement this week, do this one.

Signature verification without gotchas

Signature verification stops random internet traffic from pretending to be Stripe, GitHub, or Slack. Without it, anyone can hit your webhook URL and trigger actions like "mark invoice paid" or "invite user to workspace." Spoofed events can look valid enough to slip through basic JSON checks.

What you verify is usually the same across providers: the raw request body (exact bytes), a timestamp (to block replays), a shared secret, and the expected algorithm (often an HMAC). If any of those inputs change even slightly, the signature won’t match.

The gotcha that breaks real integrations most often: parsing JSON before verifying. Many frameworks parse and re-serialize the body, which changes whitespace or key order. Your code then verifies a different string than the provider signed, and you reject real events.

Other common pitfalls:

- Using the wrong secret (test vs production, or the wrong endpoint’s secret).

- Ignoring timestamp tolerance, then rejecting valid events when your server clock drifts.

- Verifying the wrong header (some providers send multiple signature versions).

- Returning 200 even when verification fails, which makes debugging painful.

Safe error handling is straightforward: if verification fails, reject fast and do not run any business logic. Return a clear client error (commonly 400, 401, or 403 depending on provider expectations). Log only what helps you diagnose issues: provider name, event ID (if present), a short reason like "bad signature" or "timestamp too old," and your own request ID. Avoid logging raw bodies or full headers because they can include secrets.

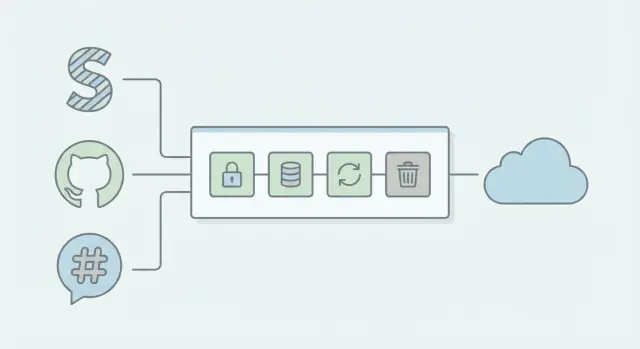

A simple webhook architecture that stays stable under load

The most reliable pattern is boring: do the minimum work in the HTTP request, then hand off the real work to a background worker.

The safe, fast request path

When Stripe, GitHub, or Slack calls your endpoint, keep the request path short and predictable:

- Verify signature and basic headers (reject fast if invalid)

- Record the event and a unique event key

- Enqueue a job (or write an "inbox" row)

- Return a 2xx response immediately

Returning 2xx quickly matters because webhook senders retry on timeouts and 5xx errors. If you do slow work (database fan-out, API calls, email) before responding, you increase retries, duplicate deliveries, and thundering-herd traffic during incidents.

Separate ingestion from processing

Think of it as two components:

- Ingestion endpoint: security checks, minimal validation, enqueue, 2xx

- Worker: idempotent business logic, retries, and state updates

This separation keeps your endpoint stable under load because the worker can scale and retry without blocking new events. If Slack sends a burst of events during a user import, the endpoint stays fast while the queue absorbs the spike.

For logging, capture what you need to debug without leaking secrets or PII: event type, sender (Stripe/GitHub/Slack), delivery ID, signature verification result, processing status, and timestamps. Avoid dumping full headers or request bodies into logs; store payloads only in a protected event store if you truly need them.

Step-by-step: a webhook handler pattern you can copy

Most webhook bugs happen because the handler tries to do everything inside the HTTP request. Treat the incoming request as a receipt step, then move real work to a worker.

The request handler (fast and strict)

This pattern works in any stack:

- Validate the request and capture the raw body. Check method, expected path, and content type. Save raw bytes before any JSON parsing so signature checks don’t break.

- Verify the signature early. Reject invalid signatures with a clear 4xx response. Don’t "best guess" what the payload meant.

- Extract an event ID and build an idempotency key. Prefer the provider’s event ID. If none exists, build a key from stable fields (source + timestamp + action + object ID).

- Write an idempotency record before side effects. Do an atomic insert like "event_id not seen before." If it already exists, return 200 and stop.

- Enqueue work and return 200 quickly. Put the event (or a pointer to stored payload) onto a queue. The web request shouldn’t call third-party APIs, send emails, or do heavy work.

The worker (safe side effects)

The worker loads the queued event, runs your business logic, and updates the idempotency record to a clear state like processing, succeeded, or failed. Retries belong here, with backoff and a cap.

Example: a Stripe payment webhook arrives twice. The second request hits the same event ID, sees the existing idempotency record, and exits without upgrading the customer again.

Retries that help instead of making things worse

Retries are useful when the failure is temporary. They’re harmful when they turn a real bug into a traffic spike, or when they repeat a request that should never succeed.

Retry only when there’s a good chance the next attempt will work: network timeouts, connection resets, and 5xx responses from your dependencies. Don’t retry 4xx responses that mean "your request is wrong" (invalid signature, bad JSON, missing required fields). Also don’t retry when you already know the event is duplicated and safely handled by idempotency.

A simple rule set:

- Retry: timeouts, 429 rate limits, 500-599, temporary DNS/connect errors

- Do not retry: 400-499 (except 429), invalid signature, failed schema validation

- Treat as success: already-processed event (idempotent replay)

- Stop quickly: dependency is down for everyone (use a circuit breaker)

- Always: cap attempts and total time

Use exponential backoff with jitter. In plain terms: wait a little, then wait longer each time, and add a small random delay so retries don’t hit all at once. For example: 1s, 2s, 4s, 8s, plus or minus up to 20% randomness.

Set both a max attempt count and a max total retry window. A practical starting point is 5 attempts over 10 to 15 minutes. This prevents "infinite retry" loops that hide problems until they explode.

Make downstream calls safe. Put short timeouts on database and API calls, and add a circuit breaker so you stop calling a failing service for a minute or two.

Finally, record why you retried: timeout, 5xx, 429, dependency name, and how long it took. Those tags turn "we sometimes miss webhooks" into a fixable issue.

Dead-letter handling: how to stop losing events forever

You need a plan for the events that won’t process even after retries. A dead-letter queue (DLQ) is a holding area for webhook deliveries that keep failing, so they don’t disappear in logs or get stuck retrying forever.

A good DLQ record keeps enough context to debug and replay without guessing:

- Raw payload (as text) and parsed JSON

- Headers you need for verification and tracing (signature, event ID, timestamp)

- Error message and stack trace (or a short failure reason)

- Attempt count and timestamps for each attempt

- Your internal processing status (created user, updated plan, etc.)

Then make replay safe. Replays should go through the same idempotent processing path as the live webhook, using a stable event key (usually the provider event ID). That way, replaying an event twice does nothing the second time.

A simple workflow helps non-technical teams act fast without touching code. For example, when a payment event fails due to a temporary database outage, someone can replay it after the system is healthy.

Keep the workflow minimal:

- Auto-route repeated failures into the DLQ after N attempts

- Show a short "what failed" message plus a payload summary

- Allow replay (with idempotency enforced)

- Allow "mark as ignored" with a required note

- Escalate to engineering if the same error repeats

Set retention and alerts. Keep DLQ items long enough to cover weekends and vacations (often 7 to 30 days), and alert a clear owner when the DLQ grows past a small threshold.

Example: preventing duplicate upgrades from a Stripe payment webhook

A common Stripe flow: a customer pays, Stripe sends a payment_intent.succeeded event, and your app upgrades the account.

Here’s how it breaks. Your handler receives the event, then tries to update the database and call a billing function. The database slows down, the request times out, and your endpoint returns a 500. Stripe assumes delivery failed and retries. Now the same event hits you again, and the user gets upgraded twice (or gets two credits, two invoices marked paid, or two welcome emails).

The fix is layered:

First, verify the Stripe signature before you do anything else. If the signature is wrong, return 400 and stop.

Next, make processing idempotent using the Stripe event.id. Store a record like processed_events(event_id) with a unique constraint. When the event comes in:

- If

event_idis new, accept it. - If

event_idalready exists, return 200 and do nothing.

Then split receipt from work: validate + record + enqueue, then let a worker perform the upgrade. The endpoint responds fast, so timeouts are rare.

Finally, add a dead-letter path. If the worker fails due to a database error, save the payload and failure reason for safe replay. Replaying should re-run the same worker code, and idempotency guarantees it still won’t double-upgrade.

After these changes, the user sees one upgrade, fewer delays, and far fewer "I paid twice" support tickets.

Common mistakes that create silent webhook bugs

Most webhook bugs aren’t loud. Your endpoint returns 200, dashboards look fine, and weeks later you notice missing upgrades, duplicate emails, or out-of-sync records.

One classic mistake is breaking signature verification by accident. Many providers sign the raw request body, but some frameworks parse JSON first and change whitespace or key order. If you verify against the parsed body, good requests can look tampered with and get rejected. The fix: verify using the raw bytes exactly as received, then parse.

Another silent failure happens when you return 200 too early. If you acknowledge the webhook and then your processing fails (database write, third-party API call, job enqueue), the provider won’t retry because you already said it worked. Only acknowledge success after you’ve safely recorded the event (or queued it) in a way you can recover.

Doing slow work inside the request thread is also a reliability killer. Webhook senders often have short timeouts. If you do heavy logic or network calls before responding, you’ll get retries, duplicates, and occasional missed events.

Dedupe bugs can be subtle too. If you dedupe on the wrong key like user ID or repository ID, you’ll accidentally drop real events. Dedupe should be based on the event’s unique identifier (and sometimes the event type), not who it’s about.

Finally, be careful with logs. Dumping full payloads can leak secrets, tokens, emails, or internal IDs. Log minimal context (event ID, type, timestamps) and redact sensitive fields.

Quick checklist: is your webhook integration safe now?

A webhook handler is "safe" when it stays correct during duplicates, retries, slow databases, and occasional bad requests.

Start with the basics that prevent fraud and double processing:

- Verify the signature using the raw request body (before JSON parsing or any body transforms).

- Create and store an idempotency record before side effects. Save the event ID (or computed key) first, then do the work.

- Return a fast 2xx response as soon as the request is verified and safely queued.

- Set clear timeouts everywhere. Handler, database calls, outgoing API calls.

- Have retries with backoff and a max attempt count. Retries should slow down over time and stop after a limit.

Then check you can recover when something still fails:

- Dead-letter storage exists and includes payload, headers you need, error reason, and attempt count.

- Replay is real. You can re-run a dead-letter event safely after fixing the bug, and idempotency prevents double effects.

- Basic monitoring is in place: counts of received, processed, retried, and dead-lettered events, plus an alert when dead-letter grows.

Quick gut check: if your server restarts mid-request, would you lose the event or process it twice? If you’re not sure, fix that first.

Next steps if your webhooks are already fragile

If you already have missed events or weird duplicates, treat this like a small repair project, not a quick patch. Pick one integration (Stripe, GitHub, or Slack) and fix it end-to-end before you touch the others.

A practical order of operations:

- Add signature verification first, and make failures obvious in logs.

- Make processing idempotent (store an event ID and ignore repeats).

- Separate "receive" from "process" (ack fast, do work in a background job).

- Add safe retries with backoff for temporary failures.

- Add dead-letter handling so failed events are saved for review.

Then write a tiny test plan you can run any time you change code:

- Duplicate delivery: send the same event twice and confirm it only applies once.

- Invalid signature: confirm the request is rejected and nothing is processed.

- Out-of-order events: confirm your system stays consistent.

- Slow downstream: simulate a timeout to confirm retries happen safely.

If you inherited webhook code generated by an AI tool and it feels brittle (hard to follow, surprising side effects, secrets in odd places), a focused remediation pass is often faster than chasing symptoms. FixMyMess (fixmymess.ai) helps teams turn broken AI-generated prototypes into production-ready code by diagnosing logic issues, hardening security, and rebuilding shaky webhook flows into a safer ingest-and-worker pattern.

FAQ

Why do I get the same webhook event more than once?

Treat duplicates as normal, not as an edge case. Most providers deliver webhooks at least once, so a timeout or a brief 500 can cause the same event to be sent again even if your code already ran once.

When should my webhook endpoint return 200?

Return a 2xx only after you’ve verified the signature and safely recorded the event (or queued it) in a way you can recover from. If you return 200 and then your database write or enqueue fails, the provider will assume everything worked and won’t retry, which creates silent data loss.

How do I prevent double-charging or double-upgrading from retries?

Use idempotency based on a stable unique key, ideally the provider’s event ID. Store that key in durable storage with a uniqueness constraint, and if you see it again, exit early while still returning success so retries stop.

How do I handle out-of-order webhook events without corrupting state?

Don’t assume ordering, even within the same provider. Make updates conditional on versioning, timestamps, or current state so an older event can’t overwrite newer data, and design handlers so each event is safe to apply even if it arrives late.

Why does signature verification fail even when the secret is correct?

Verify against the raw request body bytes exactly as received, before any JSON parsing or re-serialization. Many frameworks change whitespace or key order during parsing, and that small change is enough to make a correct signature look wrong.

Should my webhook handler do the business logic in the request thread?

A good default is to verify the signature, write an inbox/idempotency record, enqueue work, and respond immediately. Slow work like email, third-party API calls, or heavy database fan-out belongs in a worker so the provider doesn’t time out and retry.

Which failures should I retry, and which should I not retry?

Retry when the failure is likely temporary, such as timeouts, network errors, 429 rate limits, or dependency 5xx responses. Don’t retry bad signatures or invalid payloads, and always cap attempts and total retry time so failures become visible instead of looping forever.

What should I store for deduplication, and how long should I keep it?

Record a dedupe key, when you first saw it, and a processing status so you can tell received versus completed versus failed. For anything involving money or access changes, keep the dedupe record durable and long enough to cover provider retries and your own delayed reprocessing.

What is a dead-letter queue and when do I need one?

A dead-letter path is where events go after retries are exhausted so they don’t disappear. Store enough context to understand the failure and replay safely, and make sure replay goes through the same idempotent processing so replays can’t create duplicate side effects.

My webhooks are brittle and were generated by an AI tool—what’s the fastest way to fix them?

Usually you’re missing one of the core safety layers: signature verification, idempotency, fast acknowledgment with background processing, controlled retries, or dead-letter visibility. If the code was generated by an AI tool and is hard to reason about, FixMyMess can audit the webhook flow, fix the logic and security issues, and rebuild it into an ingest-and-worker pattern quickly.